Preventing depressive relapse is a major goal in the management of bipolar disorder. It has been shown that depression makes up around 72% of overall time spent ill in people with bipolar (Forte et al., 2015), and that bipolar depression specifically is associated with significant physical and mental morbidity, as well as increased mortality (Baldessarini et al., 2020).

Lithium is the first-line recommended medication for preventing bipolar depression (NICE, 2014). However, as a previous Elf blog has highlighted, prescription of lithium is declining, both in the UK and other countries (Edward, 2019). Antipsychotics, other mood stabilisers and – although not recommended by NICE – antidepressants are also often prescribed long-term for people with bipolar disorder. As recently blogged here and here, the use of antidepressants in the long-term management of bipolar disorder is controversial, with the risk of mood destabilisation associated with antidepressant monotherapy, and it is recommended that they should be prescribed for patients with bipolar disorder only in specific clinical scenarios (McIntyre et al., 2020; Pacchiarotti et al., 2013).

In a paper recently published in The Lancet Psychiatry, Ermis et al (2025) aimed to study whether the prescription of medications used in bipolar depression affect the chances of patients with bipolar disorder being admitted to hospital as a result of a depressive mood episode.

Methods

Ermis et al used a cohort study design to ascertain whether prescription of mood stabilisers, antidepressants and antipsychotics were associated with admission to hospital due to depressive illness (primary outcome), and admission to hospital due to mania or a somatic condition (secondary outcomes). Subjects and outcome data were identified from ICD-10 codes (WHO, 2019) in Swedish nationwide registers from 2006-2021, whilst data on subjects’ medications were gathered from the Prescribed Drugs Register.

A within-subjects Cox regression analysis (adjusted for time-variant covariates such as time since cohort entry and use of other psychopharmacological medications) was used to compare periods of time in which the subject was prescribed a specific medication against times in which no antidepressant, antipsychotic, or mood stabiliser were prescribed. A number of sensitivity analyses were also conducted, to ensure the robustness of the findings.

Results

105,495 people with bipolar disorder were included. The mean age of the sample was 44.2 years (standard deviation, SD 18.8), and 62.2% of the sample identified as women. Comorbidities were present in a significant minority (anxiety disorders 40.5%, substance use disorder 18.8%, personality disorders 10.4% and previous suicide attempt 10.6%).

Follow-up was commenced from the date of bipolar diagnosis and the mean follow-up time was 9.1 years (SD 5.1). At follow-up, antidepressant monotherapy was the most common exposure (used by 59,963 subjects, 56.8% of the cohort, at some point during the follow-up period), followed by mood stabiliser monotherapy (47,931, 45.4%) and antidepressant-mood stabiliser combination (46,318, 43.9%).

Overall, 16,190 subjects (15.3%) were hospitalised with a depressive episode at least once during the follow-up period; 8,066 subjects (7.7%) were hospitalised due to mania.

Decreased chance of depression-related hospitalisation

- Mood stabiliser monotherapy was the only medication group found to be associated with a decreased chance of depression-related hospitalisation compared with the prescription of no medications at all (adjusted hazards ration, aHR 0.89, 95% confidence interval, CI 0.81 to 0.98).

- Mood stabilisers combined with antipsychotics were associated with a marginally decreased chance of depression-related hospitalisation, but this was not statistically significant (aHR 0.92, 95% CI 0.85 to 1.00).

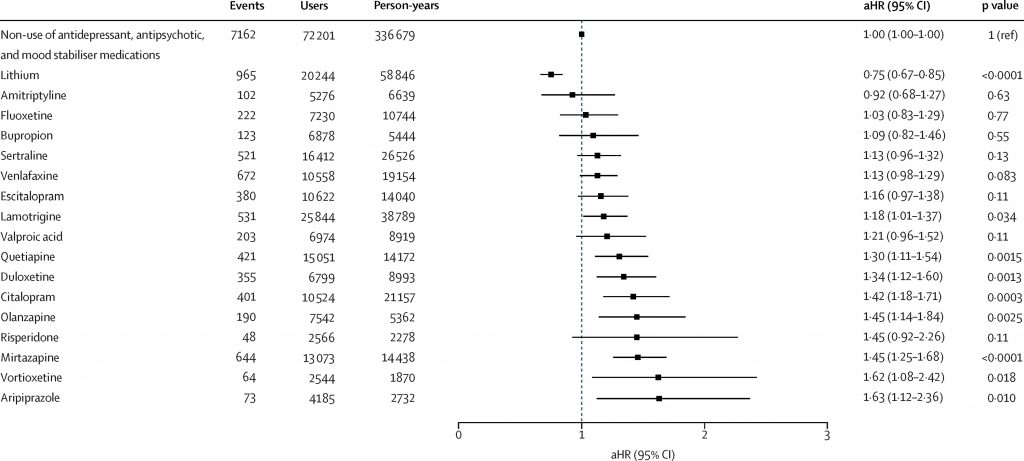

- In individual medication analysis, only lithium was associated with a decreased chance of admission due to depression in this cohort of people with bipolar disorder (aHR 0.75, 95% CI 0.67 to 0.85).

Increased chance of depression-related hospitalisation

- Apart from mood stabiliser monotherapy and mood stabilisers combined with antipsychotics, all other medication groups, either alone or in combination, were found to be associated with an increased chance of depression-related hospitalisation.

- Notably, several medications were associated with an increased chance depression-related hospitalisation, namely quetiapine, duloxetine, citalopram, olanzapine, mirtazapine, vortioxetine and aripiprazole.

Decreased chance of hospitalisation due to a somatic condition

- In terms of secondary outcomes, lithium was the only medication associated with a decreased chance of hospitalisation due to a somatic condition (aHR 0.86, 95% CI 0.80 to 0.93), with no statistically significant associations being found between the other medications and somatic hospitalisation.

Increased chance of mania-related hospitalisation

- Antidepressants-only were the only group that were associated with increased chances of hospitalisation due to mania (aHR 1.22, 95% CI 1.03 to 1.44); all other medications groups, alone or in combination, were associated with decreased chances of mania-related hospitalisation.

In individual medication analysis, only lithium showed a decreased chance of depression-related hospitalisation; all other medications were either equivocal or associated with increased chance of depression-related hospitalisation. [View full sized graphic]

Conclusions

The results of this study highlight that lithium is the only monotherapy that decreases the chances of depression-related hospitalisation in people with bipolar disorder. Additional benefits were also seen in the chances of mania-related and somatic hospitalisations, emphasising lithium’s multimodal benefits.

In contrast, certain antidepressants and antipsychotics were associated with increased chance of depression-related hospitalisation.

“Current findings supported the notion that lithium should remain the mainstay of treatment in bipolar disorder” – Ermis et al, 2025

Strengths and limitations

A cohort study design was the right method to answer this question. Cohort studies, in their observational nature, allow researchers to ascertain the effect of exposures in natural environments, making the results more generalisable to real-life situations. It also allowed the authors to compare several medications at the same time, which would not have been possible to the same extent in, for example, an RCT design.

The study population was taken from Swedish national registers and ICD-10 codes were used to identify those with bipolar disorder and the outcomes of interest. The results are therefore reliant on correct application of the ICD-10 criteria at time of diagnosis and correct coding of diagnosis into the health registers. Within these limitations, the authors were able to sample a large number of the population with a bipolar diagnosis and provide follow-up over multiple years.

In terms of the sample demographics, rates of psychiatric comorbidity and suicide attempt history were high, but this echoes the wider bipolar population (as highlighted by a previous Elf blog) and improves the generalisability of the results from this sample to real-world clinical settings. It is notable, however, that there were twice as many women than men, which is not reflective of bipolar disorder’s 1:1 male-to-female distribution and that data on ethnicity were not available, both of which limit the generalisability of the study results to particular groups.

The authors noted that by focusing on hospitalisation, the results of this study are only relevant for the most severe cases of bipolar depression and do not consider the benefits or harms that these medications may be exerting in patients who are managed entirely as outpatients. Hospitalisation is an objective, binary measure that has significant real-world implications for patients, and so it can be argued that it is still a good measure of the efficacy of these medications.

A final important consideration is that use of registry data does not always correspond exactly to behaviour. In other words, just because a prescription was written, does not mean the medication was taken. Generally speaking, however, it is probable that the majority of those prescribed a medication do take it, and the large numbers included in this sample are likely to minimise the effect that medication non-compliance in small minority may have on overall results.

Despite limitations, the large sample size and long follow-up make the results fairly generalisable to the bipolar population and important clinical scenarios.

Implications for practice

This paper reaffirms the status of lithium as “the most effective long-term treatment for bipolar disorder” (NICE, 2014). As such, it is concerning that the rates of lithium prescription appear to be declining (Lyall et al., 2019). The reasons for this are unclear, but, as a previous Elf blog highlights, it could be due to anxiety amongst patients and clinicians about the increased monitoring that is required for lithium or due to its specific adverse effect profile. It may also be related to the low cost of lithium, which may be driving the pharmaceutical industry to advertise the use of alternative, more expensive options, potentially swaying patient preference. Whatever the reason, a move away from prescribing lithium poses the risk of many patients missing out on its potential benefits.

After lithium, the second- and third-line NICE-recommended preventative medications for bipolar disorder are antipsychotic monotherapy and augmentation with valproate. This paper showed that these medications were associated with reductions in mania-related hospitalisation, but no such benefit was seen with depression-related hospitalisation. Some antipsychotics were in fact associated with increased chance hospitalisation due to a depressive episode. This may make clinicians think twice about prescribing antipsychotics or valproate long-term in bipolar disorder if the primary aim of treatment is to prevent further depressive rather than manic relapses. In many patients this will be the aim, particularly as depression makes up the majority of illness time in those with bipolar disorder (Forte et al., 2015).

So, at the very least, Ermis et al have demonstrated the need for further research in this area so that we can clarify whether current clinical guidelines for prevention of bipolar relapse are fit for purpose for all types of mood episodes, especially in those for whom lithium is not an option.

A move away from prescribing lithium poses the risk of many patients missing out on its potential benefits.

Statement of interests

No conflicts of interest to declare.

I am currently in receipt of PhD fellowship funding through a Wellcome Trust-funded study in bipolar disorder, sleep and circadian rhythm (www.ambientbd.com).

Links

Primary paper

Ermis, C., Taipale, H., Tanskanen, A., Vieta, E., Correll, C. U., Mittendorfer-Rutz, E., & Tiihonen, J. (2025). Real-world effectiveness of pharmacological maintenance treatment of bipolar depression: a within-subject analysis in a Swedish nationwide cohort. The Lancet Psychiatry.

Other references

Alsaif, M. (2017). Antidepressants for bipolar depression. National Elf Service. https://www.nationalelfservice.net/mental-health/bipolar-disorder/antidepressants-for-bipolar-depression/

Baldessarini, R. J., Vázquez, G. H., & Tondo, L. (2020). Bipolar depression: a major unsolved challenge. International journal of bipolar disorders, 8(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40345-019-0160-1

Edward, D., & Ahmed, S. (2019, 14 June 2019). Prescribing lithium for bipolar disorder: are we too scared? The Mental Elf. https://www.nationalelfservice.net/mental-health/bipolar-disorder/prescribing-lithium-bipolar-disorder/

Forte, A., Baldessarini, R. J., Tondo, L., Vázquez, G. H., Pompili, M., & Girardi, P. (2015). Long-term morbidity in bipolar-I, bipolar-II, and unipolar major depressive disorders. J Affect Disord, 178, 71-78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2015.02.011

Kalfas, M. & Leeks, P. (2024). Jury remains out on antidepressant-induced mania. National Elf Service. https://www.nationalelfservice.net/mental-health/bipolar-disorder/antidepressant-induced-mania/

Lyall, L. M., Penades, N., & Smith, D. J. (2019). Changes in prescribing for bipolar disorder between 2009 and 2016: national-level data linkage study in Scotland. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 215(1), 415-421. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2019.16

McIntyre, R. S., Berk, M., Brietzke, E., Goldstein, B. I., López-Jaramillo, C., Kessing, L. V., Malhi, G. S., Nierenberg, A. A., Rosenblat, J. D., & Majeed, A. (2020). Bipolar disorders. The Lancet, 396(10265), 1841-1856. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31544-0

NICE. (2014). Recommendations | Bipolar disorder: Assessment and Management | Guidance | NICE. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg185

Pacchiarotti, I., Bond, D. J., Baldessarini, R. J., Nolen, W. A., Grunze, H., Licht, R. W., Post, R. M., Berk, M., Goodwin, G. M., & Sachs, G. S. (2013). The International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) task force report on antidepressant use in bipolar disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry, 170(11), 1249-1262. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.13020185

Pell, C. (2013). Summing up suicide data in bipolar disorder. The Mental Elf. https://www.nationalelfservice.net/mental-health/bipolar-disorder/summing-up-suicide-data-in-bipolar-disorder/

WHO. (2019). ICD-10 Version:2019. World Health Organisation. https://icd.who.int/browse10/2019/en