“], “filter”: { “nextExceptions”: “img, blockquote, div”, “nextContainsExceptions”: “img, blockquote, a.btn, a.o-button”} }”>

Heading out the door? Read this article on the new Outside+ app available now on iOS devices for members!

>”,”name”:”in-content-cta”,”type”:”link”}}”>Download the app.

Art and meditation have a lot to say to each other. Each practice asks us to remain curious, to explore what it means to be human, and to perceive differently. Participating in making art is both physical and transcendent, bridging invisible worlds of feeling, intuition, and thought with the tangible. You might say the same about practicing meditation. And each can feel like a calling.

Poet and rock star Patti Smith once wrote, “It is the artist’s responsibility to balance mystical communication with the labor of creation.” Long before and after Smith, women artists—many overlooked by history—incorporated spiritual practices into their creative work. In fact, many used them to access visions and expressions unique to them, making a language all their own. But if art is a language, then what truths were these women speaking? What can we learn from spending time with their messages?

Hilma af Klint: Closing Your Eyes and Seeing Color

In recent years, there’s been a surge of interest in turn-of-the-century abstract artist Hilma af Klint’s bold paintings of gathering lines and clusters of circles. Though she is currently known as one of the first innovators of abstraction, she was overlooked and overshadowed by male painters in her lifetime. Yet in 2016, an exhibition of her work at New York’s Guggenheim broke attendance records and became the most-visited exhibit in the museum’s 60-year history. The same year, the Serpentine Gallery in London hosted an exhibit of the painter’s work that The Sunday Times called the “show of the year.” She’s also been the subject of numerous books, among them Hilma af Klint: Visionary and, more recently, Hilma af Klint: A Biography.

All of this is remarkable for an artist buried in a grave marked with her father’s name and who painted her first abstract work in 1906 at the age of 44. (More reasons she’s a rock star!)

Af Klint was keenly interested in spirituality and explored meditation and communion with the “divine” to create her images. She experimented with what she called automatic drawing, in which she shifted her mindset via meditation and prayer to connect with something beyond herself before turning toward her materials. Then, she created.

“The pictures were painted directly through me, without preliminary drawings and with great power,” she said. “I had no idea what the pictures would depict and still I worked quickly and surely without changing a single brushstroke.” Looking at her paintings and their geometric and spherical shapes that honor ephemeral states, you might imagine what you might also see, with your eyes closed, in a meditative state.

In her book The Other Side: A Story of Women in Art and the Spirit World, art critic and editor Jennifer Higgie looked at artists like af Klint. She wrote that “female artists who communed with the spirits were generally dismissed as kooks, while their male counterparts (in af Klint’s case, Wassily Kandinsky) were heralded as geniuses.” Though af Klint didn’t find success in her lifetime, she kept creating.

Her art, meditative practices, and innovation are hard to separate. Many of af Klint’s spiritual practices were rooted in Theosophy, a popular movement in the 1800s that helped grow yoga in the West. Theosophy prioritized yoga as a path of intuitive development. Af Klint used intuition and a sort of “second sight” to access her work.

She wasn’t the only one dipping into intuition, yoga, and meditation to access artistry.

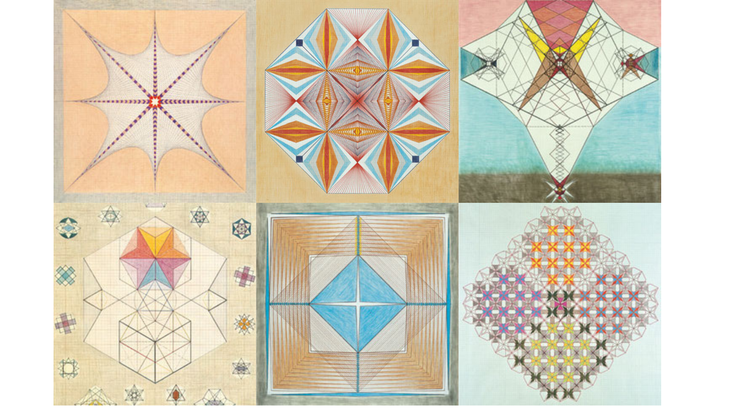

Emma Kunz: Kaleidoscopes of the Heart

A Swiss-born naturopath, artist, painter, and researcher, Emma Kunz worked in the early 1900s. Like many women of her time, she didn’t receive formal art education. Spirituality became her teacher.

A prolific maker who authored several books involving spiritual thoughts and poems, Kunz used tools such as pendulums and meditation to connect to inspiration. From there, she drafted geometric drawings to give structure to her ideas. Her paintings look like fractals of light, patterns of complex line and color in muted greens, yellows, and burnt orange.

Of her own work, she said, “Shape and form expressed as measurement, rhythm, symbol, and transformation of figure and principle.” You might think of them as psychedelic mandalas that move the viewer.

Kunz claimed the intuition she accessed while creating helped her gain insight into how her patients might heal. She used her pendulums to graph the energies she was feeling, then she drew, sketched, and painted. From there, she could discuss topics of health of the body and mind in visual ways.

Joane Kyger: Poems of the Moment

Poet Joane Kyger’s work offers a different bridge between the unseen and the seen. Kyger was a serious student and practitioner of Zen Buddhism. Her practice helped her enter a state of mind ready for poetry. Affiliated with the Beat Poets in the late 1950s and 1960s, she lived and studied meditation among monks in Japan with her husband at the time, poet Gary Snyder. She also traveled in India with Snyder and poet Allen Ginsberg. There she dipped into realms of silence via the breath in seated postures, then grabbed the pen to write.

Kyger explored how meditation can help us be more alert and awake to our own life as it’s happening and the magic that’s already around us. In her poem, “Buddhism without a Book,” she wrote about receiving teachings of spiritual wisdom from her practice and teachers. Reading her words can offer a feeling of slowing down inside, just like a meditation session might.

Well, you had to find it some

where another person passed simplicity

on to you, the practice of some syllables

the position of a seated body and you believe

a lineage of recognition of ‘mind’

not perfect, but intimate……”Try this

Lift the corners of your mouth slightly

and take three breaths.”

In her book Japan and India Journals 1960-64, Kyger wrote of sometimes feeling frustrated by being overshadowed by her spouse’s reputation. “The Bhikkus at the Mahabodhi ask Gary if his wife is an artist. Now I feel I should write poetry in front of them,” she wrote.

Kyger’s voice mattered and if space wasn’t given to her, she made it. She eventually divorced Snyder and published more than 20 collections of poetry, many with meditative themes. To read her work is to hear her voice and consider your own.

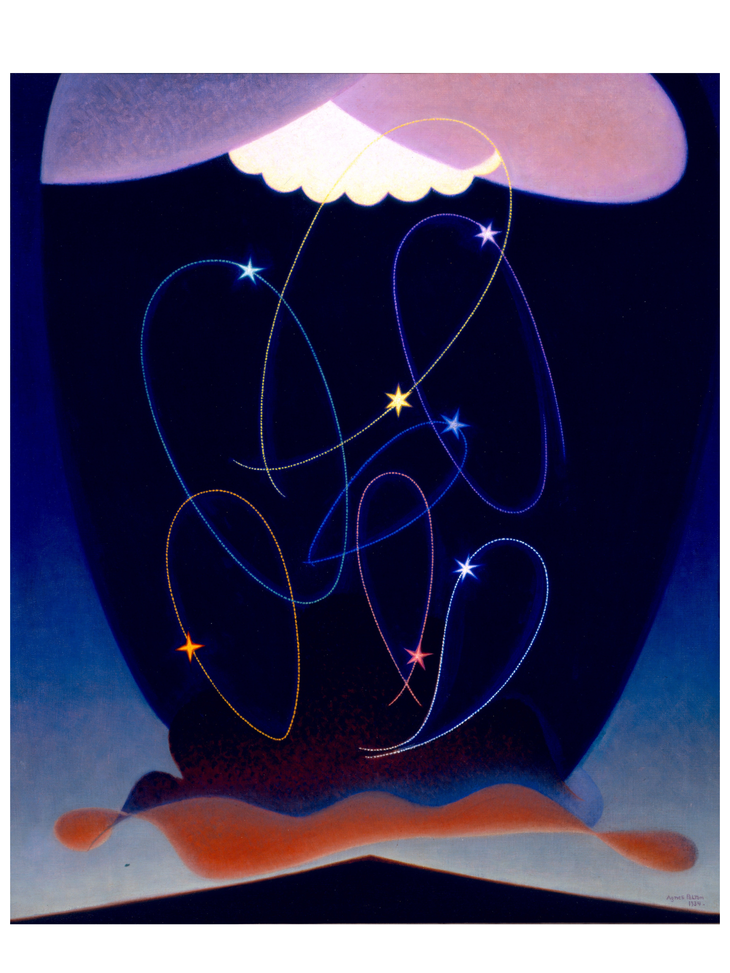

Agnes Pelton: Material of the Spirit

How do we paint energy? Artist Agnes Pelton’s colorful canvases of glowing flames, floating stars, and crystalline forms feel like a visual vocabulary of the spirit. Working out of Long Island, New York, and later in the California desert, she aimed to capture the energetic and transient states she felt during meditation and yoga. Her choice of colors are soft but vivid, dreamline but precise, like she’s trying to capture the world beneath the one we see.

Peloton’s main practice was Agni Yoga, a style developed in the 1920s by Nicholas and Helena Roerich, a Russian couple who were also artists. Rather than focusing on postural work, Agni Yoga looked at everyday life as a spiritual practice, carrying inner fire and deep intention into one’s work and letting life itself be the meditation.

Beauty, labor, and creativity were seen as sacred acts. Helena Roerich wrote, “not withdrawal, but labor and creation, are the paths of Agni Yoga.” This idea makes sense for Pelton, who used her expression of painting to explore spiritual experiences, turning outward onto the canvas as part of her practice.

Similar to other artists on this list, Pelton wasn’t well known in her lifetime. But in 2020, the Whitney Museum in New York hosted an extensive exhibit of her work, giving her the credit she deserved and referring to her as the “Desert Transcendentalist.” Pelton’s images of spiritual experiences, created through color and light, lined the walls, allowing viewers to walk through her meditative experience.

She also has an active Instagram community, despite no longer being with us in body but completely with us in energy and art, proving that the language of art is everlasting.

Alma Thomas: Color as Uplifter of the Spirit

In Alma Thomas’ work, color is a carrier of feeling. Thomas is now recognized as a significant American abstract painter and was the first African-American woman whose work was featured in the White House’s permanent collection.

Rather than precisely representing elements of nature, she relied on color and expression to capture the transcendent power of pausing to take in a sunset, a solar eclipse, or falling autumn leaves. She was inspired by the idea that nature is sacred, and that color can be used to capture the emotional states this beauty brings. “Through color, I have sought to concentrate on beauty and happiness, rather than on man’s inhumanity to man,” said Thomas. “Color is life, and light is the mother of color. Light reveals to us the spirit and living soul of the world through colors.”

The way Thomas talks about her work makes it seem almost like a meditative offering—one that can transform. “I’ve never bothered painting the ugly things in life. People struggling, having difficulty. You meet that when you go out, and then you have to come back and see the same thing hanging on the wall. No. I wanted something beautiful that you could sit down and look at. And then, the paintings change you.”

Delta Venus: Digital Portraits of the “Field of the Soul”

Of course, there are contemporary women artists working in the lineage of those above to create visual art that intersects with the mystic. One such artist is Delta Venus, an Australian-Egyptian creator and educator. Her images bloom with color and pattern, capturing auras and the living language of energy.

Sourcing her own meditation practice, intuition, and mentorship from someone she refers to as her “healer,” she illustrates the auric fields she senses around others as bright, bold prints. Though her portraits are digital, she also works with traditional paint, pencils, clay, and projections with light.

She’s also known for weaving reminder mantras in her work, lacing images with language to call the viewer to hold their higher self in esteem. In an abundance of offerings, she has an online shop with digital prints, a Higher Self deck featuring her art, and more. And, as is the contemporary way, Delta Venus also shares her vision via a podcast, Rebirth, and offers online workshops for those who are spiritually and aesthetically attuned.

“I don’t create what I see, I create what I feel in the field of the soul,” she says. “Spirituality lives inside every color, curve, and shape. For me, creation is a deeply devotional act.” Delta Venus describes art-making as becoming a conduit for creation itself. “I truly believe art carries both ancient and future memory,” she says, “helping us to remember exactly who we are beyond our material form.”

That’s the magic of art: that the material can remind us of the immaterial. Yoga holds the same wonder, joining the tangible with the unseen.

Art of Spirit and Form

It’s interesting to consider the work of these artists on their own as well as within the context of the timeframe in which they lived. With af Klint and Kunz, Higgie suggests that since their physical world was filled with sexism, judgments, and limitations, perhaps the spiritual realm was easier to live in. “If these powerful figures felt rejected by the physical world, perhaps they found shelter in the metaphysical,” she wrote.

Or maybe the world of spirit was simply another truthful reality they wanted to capture and translate for those not paying attention. Maybe the spiritual was a co-creator. A tool.

One thing’s for certain: these women taught us, again and again, that if the world isn’t welcoming, create your own. If no one is listening, speak and make anyway.

How to Channel Your Spirituality Into Art

We, too, can listen to and prioritize our intuition and use what tools we have—meditation, yoga, spiritual practices, and journaling—to feel and create bravely.

1. Keep a notebook near your yoga mat and draw, sketch, or write down what thoughts, feelings, and images come to you during your practice. Like keeping a dream journal, this exercise alone will encourage your subconscious to pay more attention to other realms of thought, feeling, and inspiration during and after practice. You may start to notice more “messages” and inspiration the more you do this.

2. Try practices such as yoga nidra or restorative yoga to calm the nervous system and tap into theta and alpha states of the mind—brain-wave activity associated with creativity, the subconscious, and deep relaxation. Don’t think about creating while in these practices; just practice being receptive. After, pick up your art tools of choice and try creating from that palpably different mind state.

3. Use the art of the artists above, or another artist you love, as objects of meditation. Spend time deeply contemplating a painting or poem, really listening to it or looking into it. Eventually, write or draw back.

Expanded credits for featured image, from top center:

Hilma af Klint. Group IX/SUW, The Swan, No. 12, 1915. Courtesy of Stiftelsen Hilma af Klints Verk. Photo by Fine Art Images/Heritage Images via Getty Images.

Portrait and artwork courtesy of Delta Venus

Detail of Emma Kunz’s ohne Titel, untitled, Komplex-081, Collection of Emma Kunz Centre.

Detail of Agnes Pelton’s Orbits, 1934. Oil on canvas. Collection of Oakland Museum of California. Gift of Concours d’Antiques, the Art Guild of the Oakland Museum of California.