Published October 21, 2025 08:27AM

Throughout America’s obsession with yoga the last half century, our perception and interpretation of it has changed considerably with each decade. The 2010s were a time of incredible change. More and more people were practicing yoga yet in many ways, it remained an exclusive practice due to issues related to accessibility, inclusivity, and financial considerations. By the end of the decade, tremendous progress had been made that would set the stage for the way we currently practice. The following article explains all that and more as part of Yoga Journal’s 50th anniversary coverage of yoga’s evolving role in America throughout the 1970s, 1980s, 1990s, 2000s, 2010s, and 2020s.

This article includes mention of body image issues which may be unsettling for some individuals.

At times, life imitates art. But the practice of yoga almost always imitates culture.

I remember taking my first yoga class when I was studying at the University of Texas at Austin. “Why not,” I figured. I needed an easy A and I was curious about a new way to move my body.

It wasn’t until years later that I moved from practicing yoga at home to a studio. There I found a steady practice that felt strong and affirming. It was 2010, a time when literally millions of others were also trying our Americanized version of this ancient tradition, and millions more would explore it before the end of the decade.

As students continued to turn to the mat for a variety of reasons, scientific researchers continued to tout the therapeutic effects of the practice. There was evidence that yoga could reduce anxiety, stress, depression, and chronic pain; enhance sleep; improve cardiovascular function; enhance flexibility, body awareness, and balance; even support recovery from addiction.

In theory, yoga could help anyone.

Yet as the practice continued to surge in popularity throughout the 2010s, the perception of what it is and who could take part also changed in ways that would shift the culture of yoga for years afterward. Although some of the changes signaled progress, others were evidence of the work that remained to be done.

Social Media and the Perception of Yoga

The extraordinary expansion of yoga that we continued to see coincided with Instagram launching in October 2010 and with the everpresent smartphone. The popular app reached 1 million users within 2 months and eventually grew to 1 billion users by June 2018. But even within months of Instagram’s launch, individuals across the planet were able to see what yoga was, who was doing it, and share their experience of it. This resulted in a visual depiction of what yoga was and who was practicing it.

This was, at the same time, beneficial and challenging. Those who had minimal exposure to yoga were able to more easily learn about it with a simple scroll. Yet how does one explain yoga through images alone?

Creators would definitely try. But attempting to communicate the nuanced and ancient tradition through visual storytelling contributed to the misperception of yoga as an aesthetic practice and false narratives around the meaning of it.

Similar to how Vogue, Glamour, and other glossy magazines promoted European standards of beauty through their covers and pages, Instagram helped normalize a visible standard of white, thin, hyperflexible yoga practitioners, altering the culture and messaging of yoga for years to come.

Yoga in America had already shapeshifted from a practice of mind, body, and spirit to one that was commonly associated with poses and exercise. Now social media seemed to define the “ideal yoga body,” and it didn’t look like mine.

Others who had been curious about the practice now had free access thanks to YouTubers like Yoga With Adriene. Practitioners were able to develop home practices with a variety of teachers and practice in short form rather than go to a studio, which was price inhibitive for many.

Yoga had now become readily available through no-cost practices and tutorials on social media platforms, yet free doesn’t mean accessible or inclusive. There were entire communities not being represented in these photos and videos.

Lack of Representation

I will never forget the day a friend said, “Have you heard about the Black, full-figured yoga teacher in Canada?”

Dianne Bondy was someone whose body resembled my own. Despite the verbal messaging in the 2010s that yoga was a tool for healing, those of us in larger and melanated bodies weren’t seeing ourselves represented in the practice.

Her decision to share her yoga practice on Instagram beginning around 2012 had everything to do with representation.

“For most of us, we cannot be what we do not see,” Bondy explained in a recent interview. “As a Black woman, I felt like I didn’t really have a choice but to show up. Who else is going to? Not everybody wants to be a trailblazer, but some of us find it necessary to right the wrong of history and exclusion.”

Seeing her felt like an invitation to become part of the conversation. And I wasn’t the only one who responded to an example.

As Einstein theorized, every action has an equal and opposite reaction. A counter culture was emerging. The “body positivity” movement had begun long before the 2010s, yet with the groundwork in place, it became more vocal during this time. The yoga space was no doubt influenced by the surrounding culture, including activist groups such as the Fat Underground, which held a visible place on social media platforms and promoted underrepresented groups on social media.

The shift in online representation of who and what a yoga body could look like coincided with a shift in the culture at yoga studios, which had previously talked about yoga for every body but not always embodied that in their teachers or teachings.

At some point in between the time I stepped into a hot yoga studio as a student in 2010 and when I started teaching in 2016, there was a noticeable shift in who was coming to the practice. I could look around and see students who were half my size as well as those who were larger than me. For the first time, I was no longer the largest body in the room.

This shift was made possible by all the bold individuals who didn’t let being the largest person keep them from practicing. As Bondy said, “Yoga is in all of us and is for all of us!”

This belief became codified when yoga teacher Jessamyn Stanley—who self-describes as Black, fat, and queer—landed on the cover of Yoga Journal in January 2019. Well, she landed on half the covers. The other half that were sent to subscribers and sold on newsstands featured master teacher and YogaWorks co-founder Maty Ezraty, someone whose body was ubiquitous in yoga imaging.

The moment that so many of us were enthused about was distorted by the magazine’s decision. Still, people like me who had never seen a body like mine on the cover of any mainstream magazine had a moment, albeit brief, of awareness. People want to see people who look like them.

Safety Shifts In the Yoga Space

Other aspects of yoga in the 2010s that similarly affected too many students were also ready for reckoning.

Many yoga teachers, both IRL and social media influencers, had become almost celebrities, a continuation of the rock star status conferred on them by students beginning in the 2000s. Must-attend yoga festivals such as Wanderlust, Bhakti Fest, and the Yoga Journal Conference showcased teachers on the main stage. These festivals, too, curated the “who’s who” of yoga and helped define what a yogi looked like.

Another problem was the inherent power dynamic between students and teachers. This was amplified with the surging followings of celebrity yoga teachers.

“People were being handed power and keys to things that we didn’t have the wisdom to manage,” explains longtime teacher and Yoga Journal contributing editor Sarah Ezrin.

More than a decade after allegations of sexual abuse caused “spiritual leader” Amrit Desai of Kripalu to resign in 1994, other abuses were revealed.

Following the death of Pattabhi Jois, founder of the Ashtanga tradition, in 2009, students stepped forward and disclosed acts of sexual misconduct allegedly committed by Jois during class. According to an article by Matthew Remski, writer and co-host of the Conspirituality Podcast, this was “enabled for decades by a devotional culture that saw him first and foremost as a benevolent father figure.”

Following that, it didn’t seem as if enough was changing in the yoga space to guard against further instances of abuse.

Teacher John Friend, the founder of the popular Anusara Yoga, tumbled from fame in 2012 following alleged scandals involving naked rituals with married students and reports of financial mishandlings, including cancelling employee’s pension funds.

In 2013, Benjamin Lorr, published Hell-Bent: Obsession, Pain, and the Search for Something Transcendence in Bikram Yoga, which began to expose the issue of students placing teachers in a role of spiritual leader without questioning their actions. Lorr had trained with Bikram Choudhury, the Beverly Hills-based founder of hot yoga whose stamp of approval could make or break teaching careers.

That same year, a former student publicly accused Choudhury of sexual assault. She would be the first of six to eventually come forward with allegations. Bikram was brought to civil court by a seventh woman, a former employee, and found guilty of wrongful termination in 2016. A judge issued a warrant for Bikram’s arrest following failure to pay millions in damages. He fled the country and continued to lead teacher trainings.

Building on the continuing #MeToo movement initiated in 2006, yoga teacher Rachel Brathen invited her then two million Instagram followers to share their stories of sexual harassment in yoga in 2017. She received more than 400 personal testimonies.

With the assistance from the US-based Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network (RAINN), Yoga Alliance, a registry of yoga teachers and schools, updated its code of conduct and posted a Statement on Sexual Misconduct in Our Community late in 2017.

Yet the yoga world still had a predator problem. More instances of alleged financial and sexual misconduct by teachers and studios continued to surface. What was changing, however, was a reassessing of the student-teacher hierarchy and its unbalanced power dynamics. These truths were finally being told in the same community in which victims had long remained silent.

News of these failings on the part of trusted leaders in yoga resulted in students needing to grapple with conflicted emotions after being confronted with the human behind the icon and the need to distinguish between the teachers and the teachings.

Yoga for All Bodies

By the end of the decade, gains continued to be made as more diverse bodies showed up to yoga. Yet we needed more than visual representation to understand that yoga was a practice that was accessible to everyone and not only the able-bodied and athletic.

What was needed were teachers who were able to lead others through poses without judgment and who knew how to adapt poses to make them welcoming of anyone, removing the divide between those who want to practice and those who could practice.

Jivana Heyman, founder of Accessible Yoga, and Amber Karnes, creator of Body Positive Yoga, were working on parallel tracks to teach yoga for all bodies, regardless of size or perceived ability. Heyman was training teachers how to make the practice more accessible and Karnes was creating a community of yoga practitioners of all sizes. Their work would continue to build as they trained teachers and students of all shapes, abilities, and ethnicities.

“Welcome everyone,” explained Heyman in a recent article for teachers. “Accessibility, diversity, and inclusion are yoga practices.”

Learning how to integrate accessible yoga teaching practices—such as the normalization of using props, relying on enabling rather than shaming language, and not insisting on adherence to overly specific alignment—would be an ongoing area of education for experienced as well as new teachers. In 2019, Bondy’s book Yoga for Everyone: 50 Poses for Every Type of Body provided a textbook.

Slowly, change was happening. As the diversity of students grew in studios, so, too, did the number of teachers reflecting that diversity. At the same time, organizations were forming to make yoga accessible to specific communities. The Veterans Yoga Project was founded in 2011 to bring specialized classes to those who had served in the military. That same year, the Prison Yoga Project, established nearly a decade prior, launched its first trauma-informed yoga teacher training to expand its reach into the prison system.

The Black Yoga Teachers Alliance (BYTA), created in 2009 by yoga teachers Maya Breuer and Jana Long as a social media group, expanded into a vibrant network of teachers, students, and enthusiasts for community, discourse, and belonging.

Elsewhere, teachers took it upon themselves to initiate Spanish-language yoga classes, such as Rosanna Rodriguez, who started leading free classes out of a church basement in New York City in 2017. Other groups also emerged, with yoga classes taking place in addiction recovery centers, cancer support organizations, older adult centers, churches, and community centers.

Students were also being introduced to the softer side of yoga—yin, restorative, meditation, and yoga nidra. As studios added more options to move slowly to schedules, students responded. More and more of us were exploring approaches to yoga that were powerful in a different way than we were accustomed.

The Yoga Industry

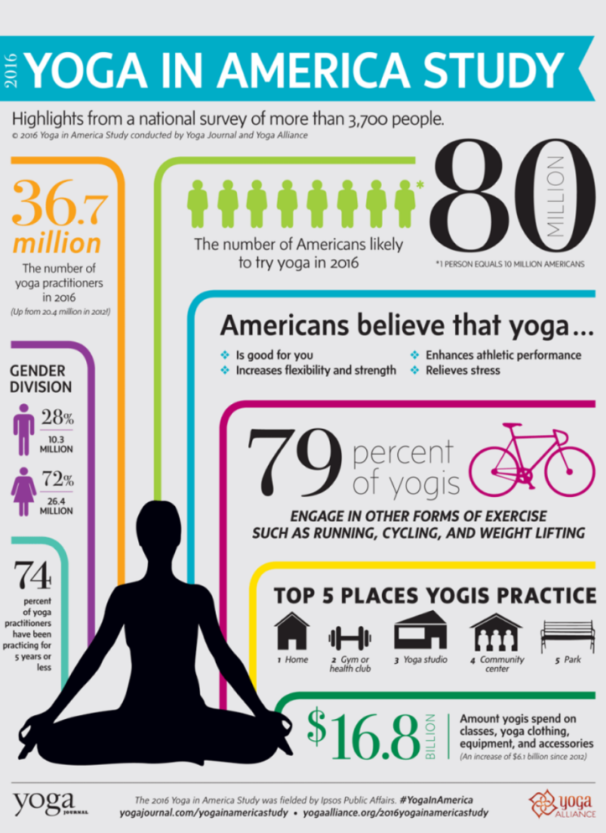

By 2016, in the U.S. alone, the number of individuals who practiced yoga surged from 21 million in 2010 to 36 million, another testament to yoga being increasingly understood as a practice for everyone.

Teachers of inclusive and accessible yoga had done much to shift the perception of yoga to that of a practice that was actually available to every body. And other teachers were rallying behind their lead.

Still, a different sort of accessibility issue arose in terms of who could afford to practice. The seeming influx of yoga studios everywhere was actually misleading. Studios remained largely relegated to affluent neighborhoods, rendering it financially inaccessible in terms of who could practice, with many studio memberships ranging from $125 to $185 a month.

To offset the lack of affordability, some studios offered now-controversial work-exchange models, often called “karma yoga,” which would help create accessibility for people who couldn’t pay for a membership. But these situations created a hierarchy in yoga studios and also drew on questionable work ethics.

At the same time, a small number of community studios were dedicated to providing inclusive and accessible yoga through donation-based and sliding-scale pricing.

And as a part of yoga was evolving into its own culture of expensive matching sets that brands told us we needed, people like me were buying Danskin for $14.99 at Walmart. Some brands—including Lululemon—limited their retail offerings to a size 12, whereas others—such as Athleta, K-Deer, and Girlfriend Collective—were offering expanded sizes and more affordable options to practitioners of any size.

Encouraging Agency

In many ways, the yoga community moved from a practice focused on the aesthetic during the 2010s toward agency, self-awareness, and inclusiveness, albeit through difficult lessons.

At the end of the decade, the expanded accessibility of yoga through representation, accessible teaching, and other inclusive practices was undeniable. If there was one achievement, it was the increase in much-needed awareness. It was a time when the yoga space had the option to continue moving toward creating something more meaningful for more people. The question is, would it?

If you are a victim of sexual assault, there are resources that can provide support at any time of day or night. In the United States, you can call the National Sexual Assault Hotline at 800-656-4673 or reach out via confidential online chat at online.rainn.org.