Published November 26, 2025 09:48AM

In Yoga Journal’s Archives series, we share a curated collection of articles originally published in past issues beginning in 1975. These stories offer a glimpse into how yoga was interpreted, written about, and practiced throughout the years. This article first appeared in the November-December 1980 issue of Yoga Journal. Find more of our Archives here.

Breathing well is not only the key to the athletic success, deep relaxation, and yoga asanas, it is one of the most important components of physiological and psychological health.

According to the historian Majumdar:

Breathing is a bridge between the voluntary and involuntary functionings of the body, between conscious mind and subconscious psyche, between body and spirit. Our breathing reflects our state of mind, elation or depression, restlessness or repose. Through proper and regulated breathing, we can gain a large measure of control over our emotions.

So how does breathing differ from pranayama, or are they the same thing?

What Does Pranayama Mean?

The practice of pranayama is believed to effect consciousness even more profoundly than the asanas do and it can be defined in several ways. By dividing the word pranayama into two parts, we note that prana means “energy” and ayama means “expansion.” Iyengar defines the word similarly, but adds that ayama also means “length, stretching, or restraint.” Tyberg defines the word slightly differently, suggesting that pra means “forth” and an is from the verb meaning “to breathe.” Thus pranayama is the control of that which brings forth breath.

Whichever definition of pranayama is accepted, the practice is much more than breathing. This distinction is clarified in the ancient text on yoga, the Hatha Yoga Pradipika, in which the commentator states that “breath does not mean the air taken in and breathed out, but the Prana, i.e., the magnetic current of breath.” So the practice of pranayama involves learning to control the energy associated with breath.

It is a good idea for the student of yoga to spend time learning to breathe well, to expand the lungs evenly and to control simple inhalation and exhalation before they advance to the more subtle process of pranayama.

When Does Breathing Become Pranayama?

While pranayama builds upon the basic physiologic process of the breath, it is more concerned with the regulation of energy which breath represents.

Alexander Lowen, creator of Bioenergetics, presents a Western view of prana:

The life force or spirit of an organism has been associated with the breath. In the Bible it is stated that God breathed His spirit into a lump of clay, giving it life. In theology, the Spirit of God or the Holy Ghost is called the pneuma, which the dictionary defines as “the vital soul or the spirit.”

In most forms of Western body work, such as Bioenergetics, work with the breath is an important part of the process. Here the breath is used in ways that will bring out emotional insights. The practice of pranayama, in contrast, is considered to be the most important tool for quieting the mind. In the first chapter of the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali, the acknowledged Father of Yoga states that the experience of irregular inspiration and expiration accompanies an agitated mind: “by expulsion and retention of breath one should overcome all obstacles, mental, and physical diseases, and make mind peaceful, happy, serene, and stable.” It is only then that it’s believed the serenity and clarity which define the state of yoga can be felt.

Whereas breathing is a simple biological process, pranayama has complex spiritual implications.

Breathing, or respiration, is described as the process of expelling carbon dioxide and inhaling oxygen in order to maintain the metabolic balance necessary for physical life. It involves the taking in and giving off of gases; the process is carried out between cells and the passing bloodstream as well as within individual cells themselves. (These are called external, internal, and intracellular respiration, respectively.) Pranayama is much more subtle than this since it connects us to the innermost aspects of being. The English word psyche is, in fact, derived from the Greek root which means “to breathe, to respire.” And the Sanskrit word atman, the innermost being, originally meant “breath” as well. Pranayama is not, therefore, just the act of taking oxygen in, but is a process whereby the yogi harmonizes the rhythm of their very energy and life force with the internal being or atman.

Although the practice of pranayama may direct the senses and mind inward, it does not imply a true withdrawal from life; rather it provides a means to experience life more fully since it helps us to approach life calmly. Yoga teaches that true harmony in our outer life follows the achievement of harmony of the body and mind; with harmony, both inner and outer perceptions become clear. Then one can act from a center of clarity and calmness, and truly live in the moment.

Preparing the Body for Purposeful Breath

The movement of the ribs is crucial to the freedom of the lungs, and therefore it is necessary for the student to prepare the ribs for pranayama by closely watching the movement of the breath. Another preparation is of course the regular practice of asanas.

This will help to stretch the connective tissues and muscles, which can inhibit rib movement. As the ribs become freer, the lungs can expand more readily. Without this preparation, it is useless and sometimes quite detrimental to practice pranayama because the mind will be agitated rather than soothed by incorrect breathing.

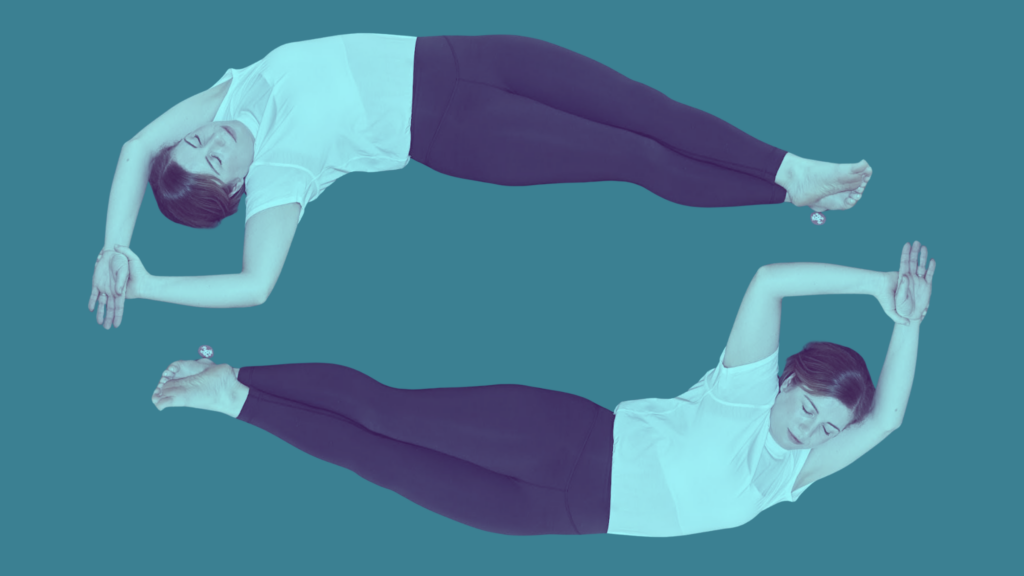

Since the ribs are attached to the spinal column, it is of crucial importance that the student learn to sit correctly for breathing exercises. Iyengar recommends a prone position tor beginners, making an innovative use of a towel, to avoid the problems most Westerners have in sitting straight-backed for 20 minutes or so.

How to Practice Pranayama

Begin by lying on the floor in Savasana (Corpse Pose). Pay meticulous attention to the alignment of the body: the legs and arms must be equidistant from the spine; the spine itself is free; the pelvis and shoulder girdles are balanced; and the head is placed so that the chin is parallel to or very slightly dropped toward the floor. A firmly rolled up towel is then placed under the lower floating ribs. This lifts the rib cage and allows the lumbar (lower) spine to extend. Again, the position of the head should be checked. The towel should not interfere with the repose of the shoulder joints. The eyes are kept closed at all times during the practice.

Begin by becoming aware of the movement of the breath, noting the rhythm of inhalation and exhalation. After the mind has become quieter, try to equalize the inhalation and the exhalation. No strain should be felt; no pressure should be exerted in the thoracic cavity; the thighs and abdomen must remain passive. Instead of trying to make the shorter of the two processes—inhalation and exhalation—longer, work to make the longer one match the shorter. In other words, if you have trouble making the exhalation as long as the inhalation, then try to make the inhalation match the length of the exhalation. Gradually both will lengthen.

The idea is to make both breaths as long, smooth, and even as possible. This is called “sama vritti, or equal disturbance or movement in the breath. Allow a natural pause between inhalation and exhalation. Practice for five minutes, in the beginning, and gradually work up to 15. Never follow a vigorous asana practice with pranayama. Choose a time when the mind is less disturbed, either first thing in the morning before asana practice, or preferably later, in the afternoon.

Follow this practice with a five- to 15-minute Savasana. The practice of sama vritti should produce feelings of equanimity and poise; even at this beginning stage, it should never produce feelings of agitation. If this occurs, practice Savasana and shorten the time of sama vritti. For the best results, try to practice every day. Concentrate on the quality of the breath, feeling its subtleness and presence, rather than on how long the inhalation and exhalation are becoming. They will lengthen on their own. This lying practice can be done for years with beneficial results. It is especially recommended for the practitioner who does not have the supervision of a competent teacher.