Ever since the days of Hippocrates, 2,400 years ago, fasting has been offered as a treatment for acute and chronic diseases, based on the observation that when people get sick they frequently lose their appetite.

Along with fever, decreased food consumption is one of the most common signs of infection. Often regarded as an undesirable manifestation of sickness, it’s actually an active, beneficial defense mechanism. As I discuss in my video Fasting for Cancer: What about Cachexia, chronic under-nutrition can impair our defenses, but data suggest that, in the short-term, immune function can be enhanced by lowering food intake.

Researchers have shown that the blood from starved mice was nearly eight times better at killing off the invading bacteria in a petri dish, dramatically boosting the capacity of their white blood cells to kill off the pathogens. What about people? And what about cancer?

Does Fasting Help Our Natural Killer Cells Fight Cancer Cells?

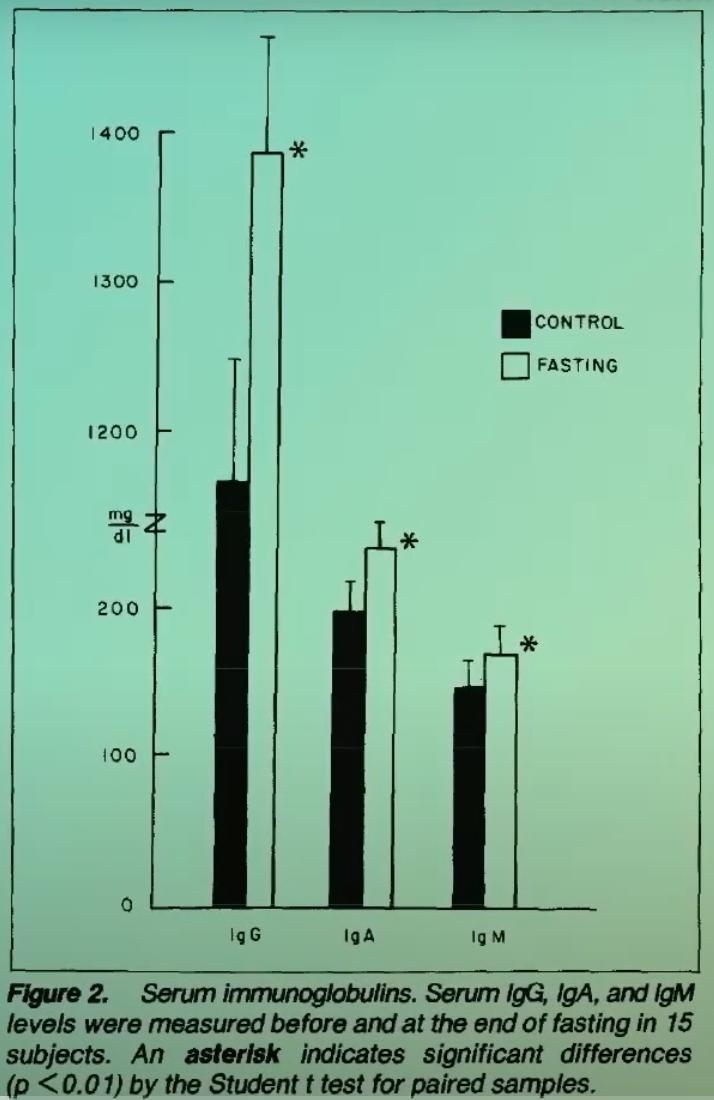

When study participants fasted for two weeks on an 80-calorie-a-day diet, not only did their white blood cells show the same kind of boost in bacteria-killing ability and antibody production, but their natural killer cell activity increased by an average of 24%. This is especially interesting because our natural killer cells don’t just help clear infections, but they also kill cancer cells. In fact, that’s how the researchers measured natural killer cell activity; they pitted them against K562 cells, which are human leukemia cells.

Fasting is said to improve anticancer immunosurveillance, or, more poetically, by “stimulating the appetite of the immune system for cancer.” So, why isn’t fasting used more to treat cancer? Because so much about cancer care revolves around keeping people’s weight up to try to counteract the cancer-wasting syndrome.

What Causes Cancer Cachexia?

Until recently, fasting therapy was not considered to be a treatment option in cancer, related to the fact that a common therapeutic goal in palliative cancer treatment is to avoid weight loss and counteract the wasting syndrome known as cachexia, which is the ultimate cause of death in many cancer cases.

Tumors are voracious, rapidly expanding and in need of a lot of energy and protein, so cancer metabolically reprograms the body to start breaking down to feed its tumors. It does this by triggering inflammation throughout the body. It’s not just that people lose their appetite. “The fundamental difference between the weight loss observed in CC [cancer cachexia] and that seen in simple starvation is the lack of reversibility with feeding alone.”

Therapeutic nutritional interventions to correct or reverse cachexia frequently fail. The best treatment for cancer cachexia, therefore, is to treat the cause and cure the cancer. In fact, maybe forcing extra nutrition on cancer patients could be playing right into the tumor’s hands. Like in pregnancy when the fetus gets first dibs on nutrients even at the mother’s expense, the tumor may be first in the feeding line. Maybe our loss of appetite when we get cancer is even a protective response.

Is Chemotherapy Enough?

As I discuss in my video Fasting Before and After Chemotherapy and Radiation, for the past 50 years, chemotherapy has been a major medical treatment for a wide range of cancers. Its main strategy has been largely based on targeting cancer cells, by means of DNA damage caused in part by the production of free radicals. Although these drugs were first believed to be very selective for tumor cells, we eventually learned that normal cells also experience severe chemotherapy-dependent damage, which can lead to dose-limiting side effects, including bone marrow and immune system suppression, fatigue, vomiting, diarrhea, and in some cases, even death.

If you do survive chemotherapy, the DNA damage to normal cells can even lead to new cancers down the road. There are cell-protecting drugs that have been tried to reduce the side effects so you can pump in higher chemo doses, but these drugs have not been shown to increase survival––in part because they may also be protecting the cancer cells. What about instead fasting for cellular protection during cancer treatment?

Fasting and Chemotherapy

Many may not recognize the role fasting can play in cancer prevention and treatment. Short-term fasting before and immediately after chemotherapy may minimize side effects, while, at the same time, it may actually make cancer cells more sensitive to treatment. That’s exciting!

During deprivation, healthy cells switch from growth to maintenance and repair, but tumor cells are unable to slow down their unbridled growth, due to growth-promoting mutations that led them to become cancer cells in the first place. This inability to adapt to starvation may represent an important Achilles’ heel for many types of cancer cells.

As a consequence of these differential responses of healthy cells versus cancer cells to short-term fasting, chemotherapy causes more DNA damage and cell suicide in tumor cells, while potentially leaving healthy cells unharmed. Thus, short-term fasting may protect healthy cells against the toxic assault of chemotherapy and cause tumor cells to be more sensitive––or at least that’s the theory.

Researchers found that, in rodents, fasting alone appears to work as well as chemotherapy. What’s more, unbridled tumor growth was also knocked down by radiation therapy—and even more so after the combination of radiation and alternate-day fasting. However, alternate-day fasting alone seemed to do as well as radiation. These data are exciting, but for mice with breast cancer. What about people?

Fasting Put to the Test Against Cancers

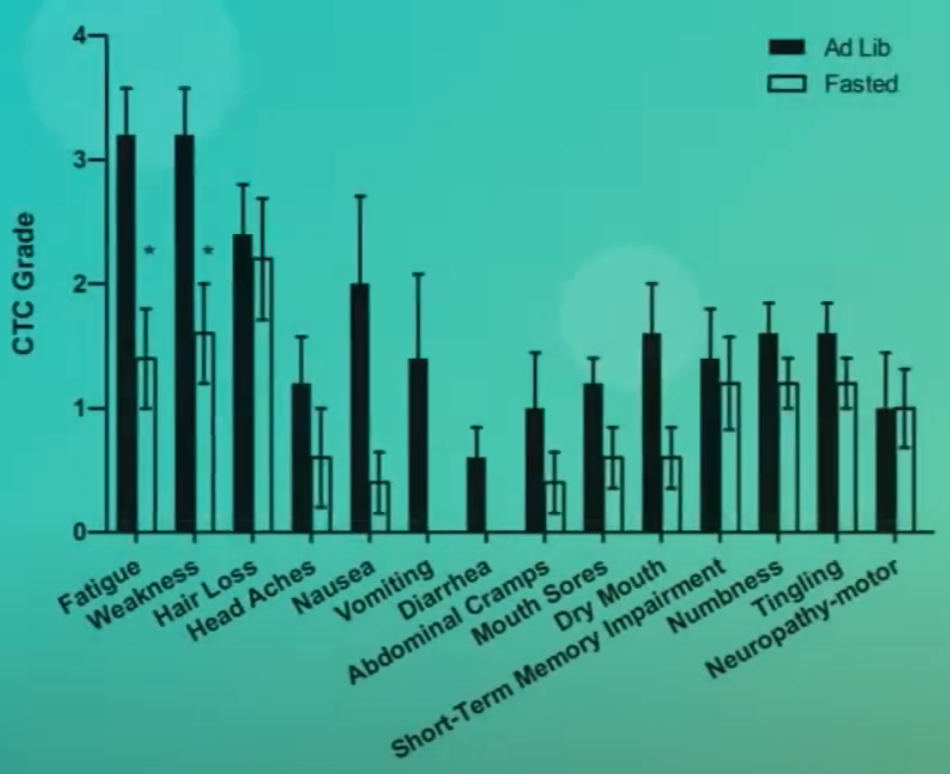

As I discuss in my video Fasting Before and After Chemotherapy Put to the Test, several patients diagnosed with a wide variety of cancers elected to undertake fasting prior to chemotherapy and share their experiences. They reported a reduction in fatigue, weakness, and gastrointestinal side effects while fasting and felt better across the board, with zero vomiting. The weight lost during the few days of fasting was quickly recovered by most of the patients and did not lead to any discernable harm. So, overall, fasting under care seems safe and potentially able to ameliorate side effects.

In a randomized clinical study, breast and ovarian cancer patients fasted from 36 hours before chemotherapy until 24 hours after, and fasting did appear to improve quality of life and fatigue. However, another study found no such beneficial effects. There did appear to perhaps be less bone marrow toxicity, given the higher counts of red blood cells and platelet-making cells. But no benefit when it came to saving white blood cells—the immune system cells—so that was a disappointment. Perhaps they didn’t fast long enough?

A systematic review of 22 studies found that, overall, fasting may not only reduce chemotherapy side effects (like organ damage, immune suppression, and chemotherapy-induced death), but it may also suppress tumor progression, including tumor growth and metastasis, resulting in improved survival. But, nearly all the studies were on mice and dogs. The studies on humans were limited to evaluating safety and side effects. The tumor-suppression effects of fasting––for example, its influence on tumor growth, metastasis and prognosis––sadly, were not evaluated.

Does Fasting Make Chemo More Effective?

As I discuss in my video Fasting-Mimicking Diet Before and After Chemotherapy, short-term food withdrawal during chemotherapy may begin to solve the long-standing problem with most cancer treatments: how to kill the tumor without killing the patient. Short-term fasting––for example, for 48 hours before chemo and 24 hours afterwards––may reduce side effects, so-called “chemotherapy-induced toxicity.” However, the potential tumor-suppressing effects of fasting have still not been thoroughly evaluated.

Some argue that reducing chemo’s side effects alone could improve efficacy, since patients could withstand higher doses. For example, the heart and kidney damage associated with the widely prescribed anti-cancer drugs limit their full therapeutic potential. It’s not clear, though, that maximizing the tolerated chemo dose would achieve longer survival or better quality of life. For now, I think we should just be satisfied with the fewer side effects for fewer side effects’ sake.

How Does Fasting Work?

Fasting can reduce the levels of insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1), a cancer-promoting growth hormone. The reduced levels of IGF-1 mediate the differential protection of normal cells and cancer cells in response to fasting and improve chemo’s ability to kill cancer but spare normal cells.

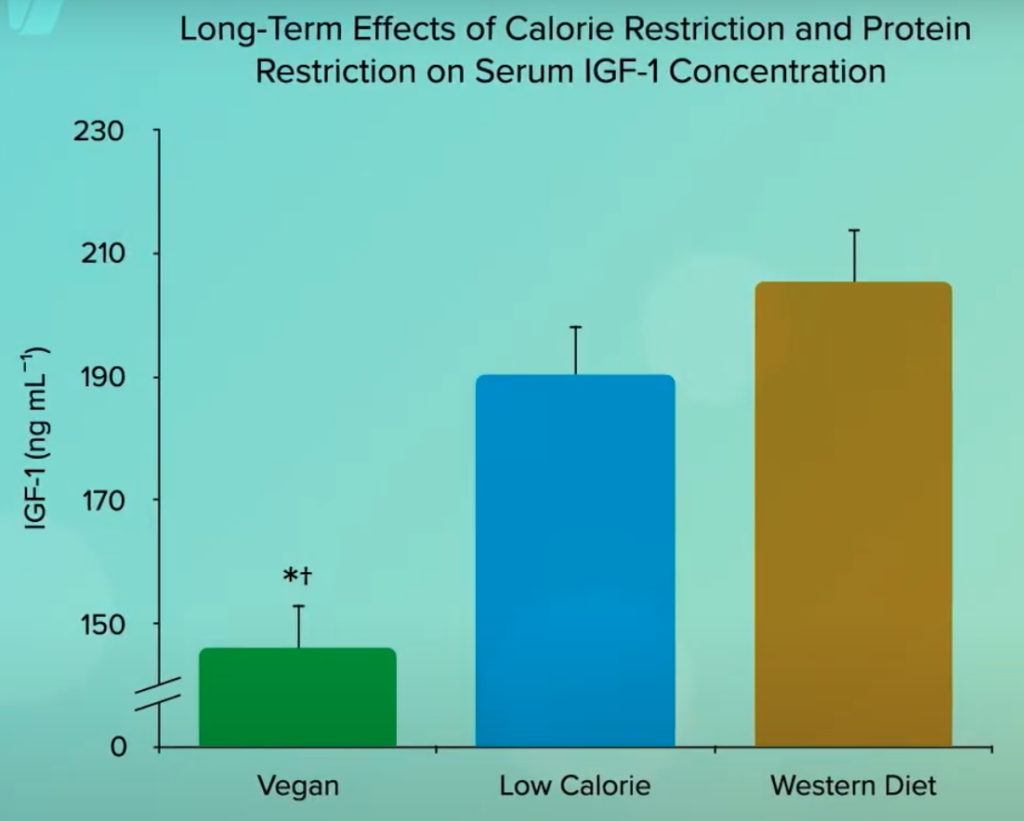

So, reducing IGF-1 signaling may provide dual benefits by protecting normal tissues while reducing tumor progression. It may even help prevent the cancer in the first place. But fasting isn’t the only way to drop IGF-1 levels: A few days of fasting can cut levels in half, but that’s largely because protein intake is being cut. Protein is a key determinant of circulating IGF-1 levels in humans––suggesting that “reduced protein intake may become an important component of anticancer and antiaging dietary interventions,” particularly a reduction in animal protein.

Lowering Protein Intake to Lower IGF-1

If you compare those who eat strictly plant-based diets and get about the recommended daily intake of protein (0.8 grams per kg of body weight) to individuals who are just as slender but consume the higher amount of protein more typical to Americans, going on a calorie-restricted diet may lower IGF-1 a little, but eating a plant-based diet can lower it even more than going low calorie.

So, not only may a diet centered around whole plant foods down-regulate IGF-1 activity, potentially slowing the aging process, but it may be a way of turning anti-aging genes against cancer.