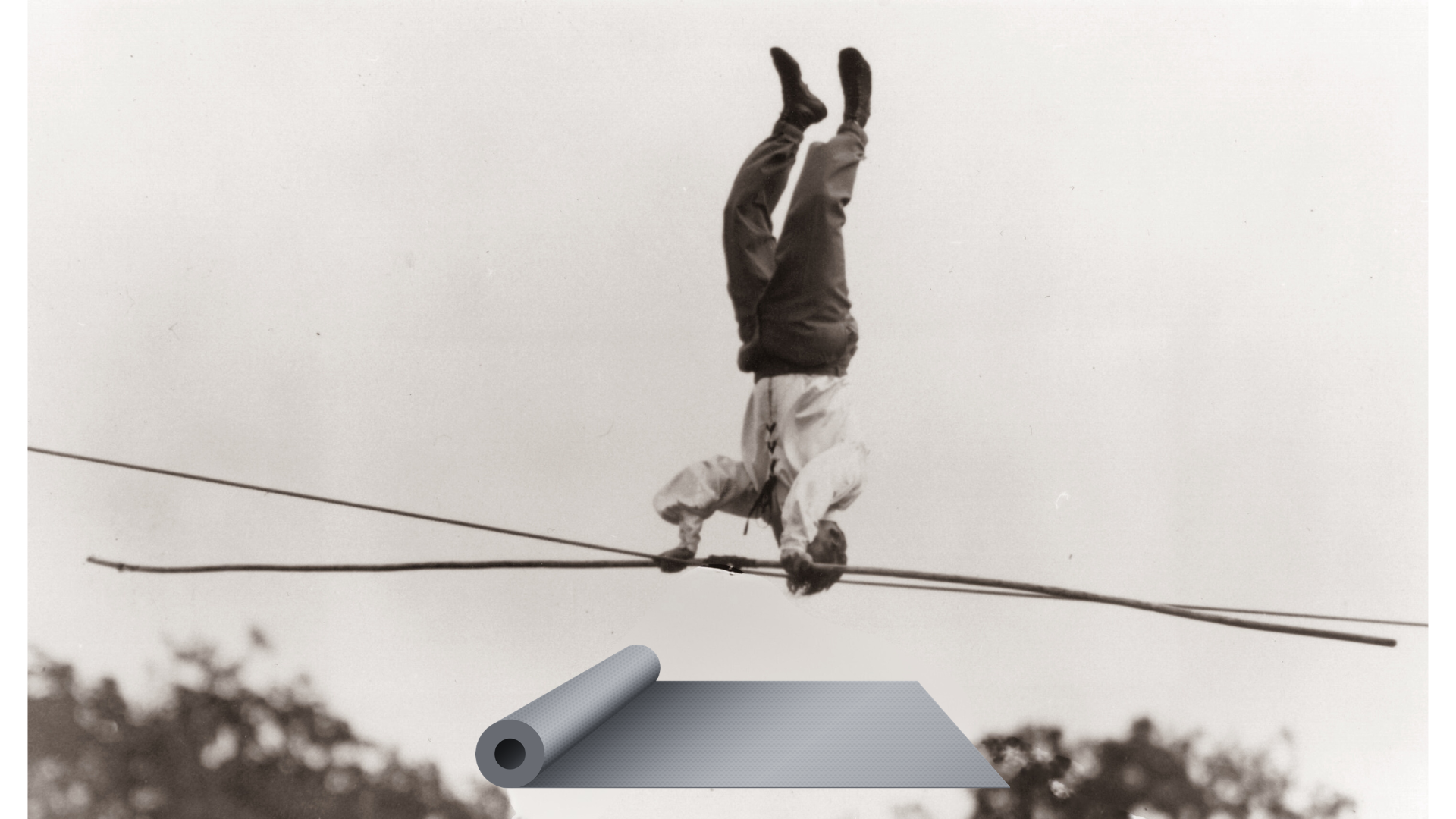

Published January 23, 2026 04:16PM

Yoga Journal’s archives series is a curated collection of articles originally published in past issues beginning in 1975. This article first appeared in the January 1984 issue of Yoga Journal.

Yogis discovered the joys of twisting long before the dance craze captured America’s attention in the early ’60s. Improved abdominal circulation and toning of the abdominal muscles, relief of pain in the hips and shoulders, increased blood flow to the spinal nerves, and greater elasticity and strength of the spine are some of the many physiological benefits derived from practicing the twisting asanas.

Of major importance also are the effects on the spinal discs, the shock absorbers that separate the vertebral bodies. The rotation of the spine moving into a twist compresses the soft-tissue discs; the de-rotation coming out of the twist releases them. This squeezing and releasing produces a sponge-like action that allows the disc cells to absorb fresh nutrients and eliminate metabolic wastes. Without this action, the discs will slowly dehydrate and eventually degenerate, causing the shrinking height so often seen in older adults.

However, the compression of the discs in twisting exacerbate any disc pathology. Thus, twists are contraindicated for anyone with neurological indications of disc troubles (numbness or sharp tingling pain in the lumbar, pelvic, or leg regions). The safe practice of twists requires precise kinesiology, i.e., clean movement of the bones. Each joint should open and extend from its center, with each bone (and its corresponding connective tissue) having independent intelligence. (In yoga, intelligence can be defined as the harmonious interaction of the voluntary nervous system and gravity to produce efficient balancing and movement of the body.)

Although it is difficult to experience the intelligence at this level without years of practice, an understanding of the correct movements leads to refined internal investigations into one’s own individual kinesiological patterns.

Anatomy of Twists

On the musculoskeletal level, every asana has two main components: the position of the bones and the precisely patterned flow of intelligence through the muscles. The bones are aligned in the gravitational field to completely support the weight of the body. The flow patterns of the muscular intelligence hold the bones securely in place while opening and extending the body in all directions.

The spinal column is the primary recipient of this extension. These flow patterns can be seen as combinations of creative and receptive intelligences. The appendages (the arms, the legs, and all their component parts) function actively, creating the pose by interacting with the ground or floor and any other useful prop (walls, chairs, even other appendages). The torso (including the head) receives the rebounding lift and extension created by the appendages.

The creative and receptive intelligences intersect at two major centers. The energy of the legs flows into the spine through and from the center of the pelvis (ie., the hara, or second chakra); the energy of the arms flows into the spine through and from the heart chakra in the center of the chest.

The second and fourth chakras are the two creative centers for postural intelligence. All twists are created here.

In standing and sitting twists, the pelvic and heart centers rotate in the same direction. In inverted and lying twists, the two centers rotate in opposite directions. The result is a continuously spiraling extension of the spinal column that opens each vertebral joint smoothly and sequentially.

Twists begin with a rotation of the pelvis around the femur in any of three possible axes: (1) a forward-bending/back-bending movement around an axis through the hip joints; (2) a side-bending movement around an axis running through the sacrum and lower abdomen; and (3) a rotational movement around the axis through the spinal column. This last action shapes the flow patterns of all twists.

Common Pain Points in Twists

Limited pelvic movement caused by tight and restricted joints—common in many people—may force the spinal column into a creative rather than a receptive mode. However, the spine should remain receptive at all times; i.e., movement should never originate in the spinal column. The spine should always soften and lengthen in response to action or movement from the arms and legs.

When the twisting pattern is blocked in the pelvis, the spine loses its connection to the legs. To complete the pose, the spine must then generate another twisting action, usually at the sacroiliac joints. Because these delicate joints are not designed to rotate, pain and joint dysfunction often results. To avoid such difficulties, (1) maximize the movement of the hip joints (by practicing hip-opening poses and by understanding all the possible movements of the hip—flexion, extension, adduction, abduction, and internal and external rotation) and (2) get to know your own limitations in movement.

Do not force the spine to twist when the hip joints are stuck; instead, work on releasing the blockage at the hip joint while twisting.

From the pelvis, the twist flows into the lumbar region, where the shape of the lumbar vertebrae limits their rotation to approximately 60 degrees. This part of the twist is facilitated by maximum space between the bones and by a normal curve. The lumbar region—which includes the abdomen and the diaphragm and corresponds to the third chakra—must continuously soften and lengthen. Postural movement should not originate here.

Unfortunately, the postural intelligence of many people is centered in the abdomen, and the resulting tension in the abdominal muscles spills over into the diaphragm, restricting movement in the breath and spine. (Note that the abdominal muscles should provide structural support. This elasticity originates in the muscles themselves and is quite different from the tension caused by the mind.)

The thoracic vertebrae have double the rotational range of the lumbar vertebrae (roughly 120 degrees); thus much more of the twist is experienced here. The shoulder girdles and arms feed energy into this region to increase the depth of the twist. The shoulder blade must be completely mobile to fully utilize the arm’s potential. When the scapula is stuck to the body, the shoulder joint overworks, but very little of the twist reaches the spine. For the spine to rotate from the heart center, the energy must flow smoothly from the upper arm into the scapula and then into the rib cage.

The rotational wave generated by the upper limbs must harmonize with the wave flowing from the pelvis, blending to produce one spiraling movement. The receptive lengthening of the third chakra region allows the harmonious interaction of the second and fourth chakra regions. The neck and head should receive the spiraling wave from the heart center. Unfortunately, the cervical vertebrae, which can rotate up to 180 degrees, often “race ahead” of the thoracic vertebrae.

Only the arms and legs should be used to create the asanas, however, and the practitioner must overcome a strong tendency to create the twist with the head. The triceps and quadriceps muscles are the major power plants of the musculoskeletal system; the spine is an antenna aligned and directed by the intelligence of the arms and legs.

What to Know About Side-Bending in Twists

Twisting poses are further complicated by the fact that rotation of the spinal column is always accompanied by side bending of the vertebral bodies, and vice versa. (Care should be taken, in doing twists, not to exaggerate these side-bending movements.) In the cervical regions, rotation and side bending occur to the same side.

Rotation to the right also produces side bending to the right. To minimize side bending while rotating the neck, lengthen the muscles on the side of the neck toward which you are turning and shorten the neck muscles on the opposite side. Interestingly enough, rotation in the thoracic and lumbar regions is accompanied by side bending in the opposite direction. Rotating to the left produces a side bend to the right, and vice versa. Thus, to evenly extend both when twisting to the left, actively lengthen the right side of the spine while the left side resists. When twisting to the right, actively lengthen the left side. These adjustments should be made without inducing tension in the spinal muscles.

Where the Twist Happens in the Spine

Kinesiological precision comes from awareness at the level of the bones. In addition, one should have some sense of how the twists are affecting the spinal muscles. All spinal muscles should soften and lengthen to receive the flow of the twist. The flow pattern can be experienced in three major layers of back muscles.

In the outermost layer, the fibers run almost perpendicular to the spine. This group includes the latissimus, the trapezius, the serratus, and the rhomboids and helps connect the actions of the upper limbs and the spinal column. The fibers of the middle layer run parallel to the spine from the pelvis to the skull. These erector spinae muscles, when softened and lengthened, produce an elongation of the spinal column.

The innermost layer is composed of shorter muscles that connect the spinous and transverse processes of adjacent and nearly adjacent vertebrae in criss-crossing patters along most of the length of the spine. Vertebral rotation occurs at this level, and softening and releasing here produces a complete release of the spine and maximum freedom of the vertebrae.

Working with the breath and using visualizations of softening and lengthening can help increase the receptivity of the spine. In twists, as in other asanas, both left-brain and right-brain conscious-ness come into play. The analytical left brain probes the details of the pose and explores the various kinesiological possibilities; the right brain experiences and creates patterned wholes, capturing the flowing essence each posture.

When these two aspects of consciousness are working together harmoniously, the mind can constantly refine and adjust the pose while maintaining a continuous flow of intelligence. This integration requiring great concentration and stillness of mind—is one of the challenges of asana practice and provides a fertile field for Self-unfolding.

A Twisting Sampler

The following section offers a variety of twists. Seeing their underlying unity will bring sensitivity and refinement to the practice of all asanas. Be sure to practice twisting to both sides; only one side of the pose is shown because of space limitations. In all twists where the upper arm works against the outer thigh or knee, there is a tendency to shorten the front spine when positioning the arm. Watch for this, and continuously lengthen the frontal spine at all times.

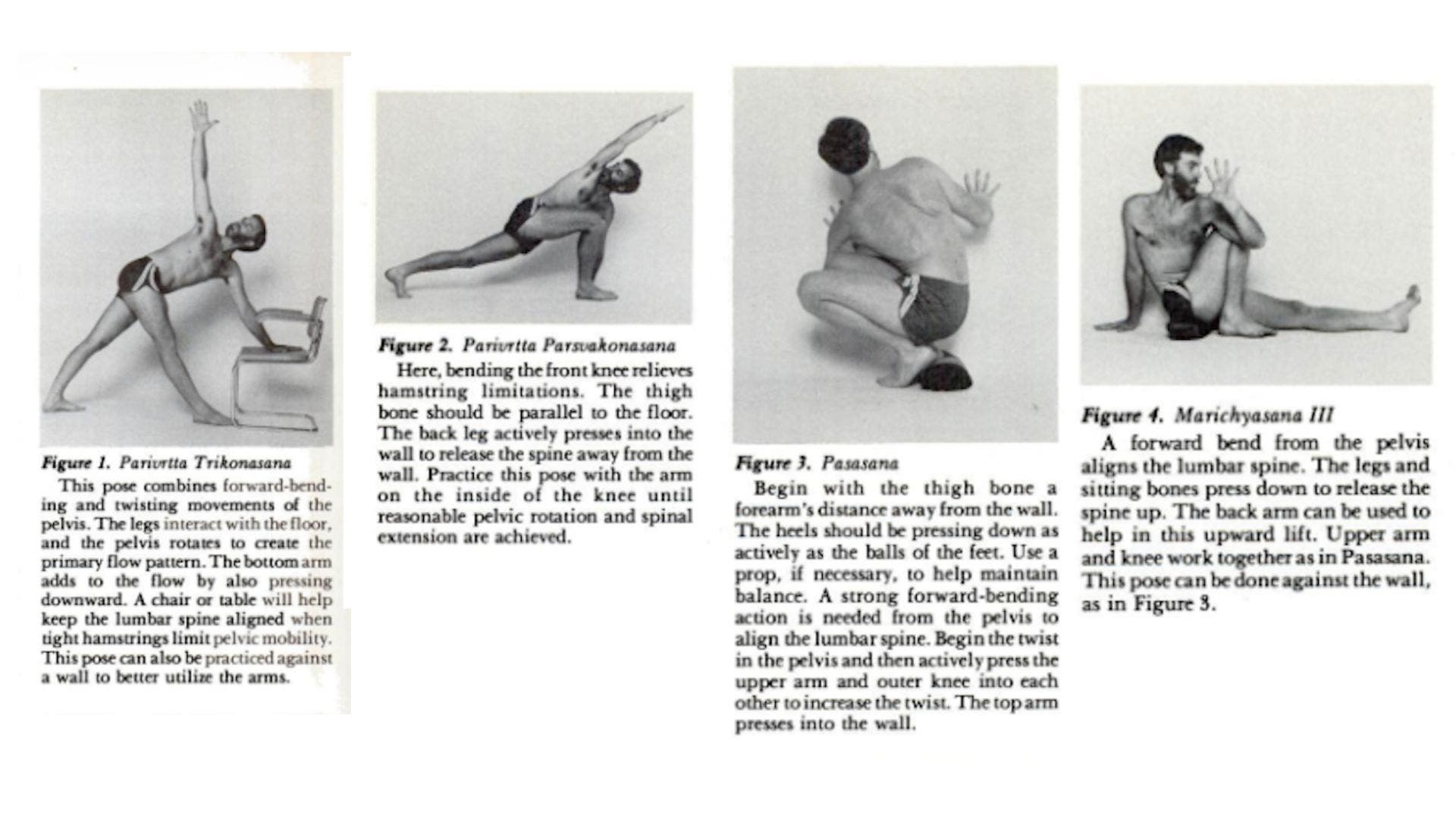

Figure 1. Pariurtta Trikonasana

Keep the diaphragm soft, and allow the breath to flow freely. Let the poses flow from the center of the body outward as the mind moves from the outside inward. (For complete instructions on all of these twists except Ramanand’s Twist and Bent-Knee Crocodile Twist).

This pose combines forward-bending and twisting movements of the pelvis. The legs interact with the floor, and the pelvis rotates to create the primary flow pattern. The bottom arm adds to the flow by also pressing downward. A chair or table will help keep the lumbar spine aligned when tight hamstrings limit pelvic mobility. This pose can also be practiced against a wall to better utilize the arms.

Figure 2. Pariurtta Parsvakonasana

Here, bending the front knee relieves hamstring limitations. The thigh bone should be parallel to the floor. The back leg actively presses into the wall to release the spine away from the wall. Practice this pose with the arm on the inside of the knee until reasonable pelvic rotation and spinal extension are achieved.

Figure 3. Pasasana

Begin with the thigh bone a forearm’s distance away from the wall. The heels should be pressing down as actively as the balls of the feet. Use a prop. if necessary, to help maintain balance. A strong forward-bending action is needed from the pelvis to align the lumbar spine. Begin the twist in the pelvis and then actively press the upper arm and outer knee into each other to increase the twist. The top arm presses into the wall.

Figure 4. Marichyasana III

A forward bend from the pelvis aligns the lumbar spine. The legs and sitting bones press down to release the spine up. The back arm can be used to help in this upward lift. Upper arm and knee work together as in Pasasana.

This pose can be done against the wall, as in Figure 3.

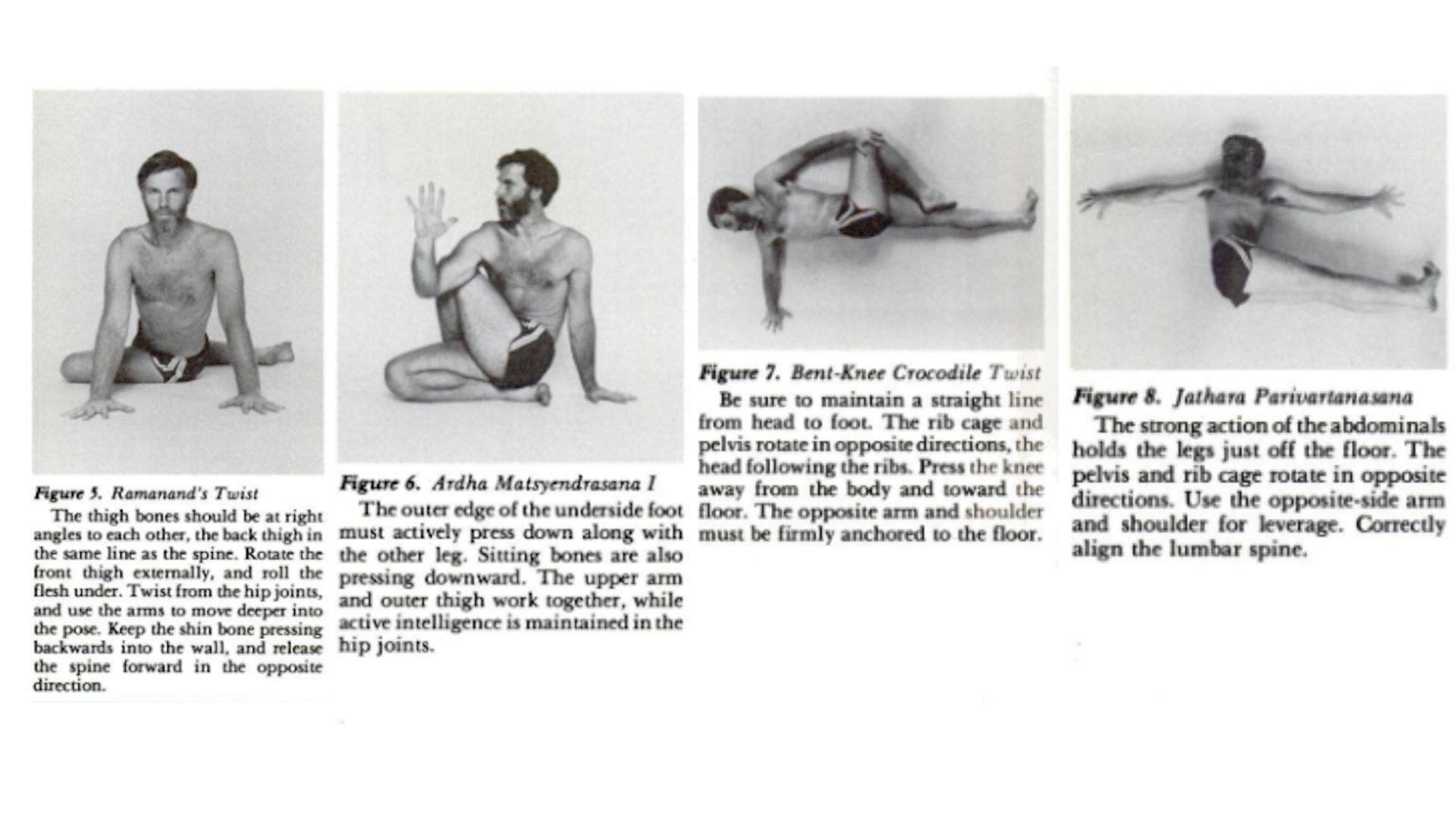

Figure 5. Ramanand’s Twist

The thigh bones should be at right angles to each other, the back thigh in the same line as the spine. Rotate the front thigh externally, and roll the flesh under. Twist from the hip joints, and use the arms to move deeper into the pose. Keep the shin bone pressing backwards into the wall, and release the spine forward in the opposite direction.

Figure 6. Ardha Matsyendrasana

The outer edge of the underside foot must actively press down along with the other leg. Sitting bones are also pressing downward. The upper arm and outer thigh work together, while active intelligence is maintained in the hip joints.

Figure 7. Bent-Knee Crocodile Twist

Be sure to maintain a straight line from head to foot. The rib cage and pelvis rotate in opposite directions, the head following the ribs. Press the knee away from the body and toward the floor. The opposite arm and shoulder must be firmly anchored to the floor.

Figure 8. Jazhara Parivarianasana

The strong action of the abdominals holds the legs just off the floor. The pelvis and rib cage rotate in opposite directions. Use the opposite-side arm and shoulder for leverage. Correctly align the lumbar spine.

Figure 9. Parsva Sirsasana

This pose begins in the arms and shoulders. Strong resistance is needed from the armpit of the side toward which the pelvis is turning. The pelvis and ribs rotate in opposite directions.

The entire leg of the same side (right leg when twisting to the right) must also resist by internally rotating in the hip socket. The opposite-side leg lengthens more to maintain even spinal extension.

Figure 10. Parsva Sarvangasana

Here, a strong back-bending action in the pelvis keeps the lumbar spine correctly aligned.

The rib cage and pelvis again turn in opposite directions. When the legs are extending to the right side, the left hip stretches out and drops down toward the floor. The rib cage turns to the right shoulder.

The keys to balancing are a strong lifting of the sternum (the heart center is the pivotal point of the pose); the anchoring of the opposite arm and shoulder to help counterbalance the weight of the legs; and the placement of the supporting hand on the pelvis.

Some prefer placing the hand directly under the sacrum and coccyx in the center of the pelvis; others use a slightly off-center position.