“], “filter”: { “nextExceptions”: “img, blockquote, div”, “nextContainsExceptions”: “img, blockquote, a.btn, a.o-button”} }”>

Heading out the door? Read this article on the new Outside+ app available now on iOS devices for members!

>”,”name”:”in-content-cta”,”type”:”link”}}”>Download the app.

If you practice yin yoga, chances are you’re familiar with the proliferation of creative, fanciful, and sometimes silly names for the poses. Cat Pulling Its Tail. Marauding Bear. Twisted Roots. Dragon with Open Wings. Graceful Bow. Upswan.

Many students and teachers, including myself, find this to be an endearing aspect of the practice. But the array of yin yoga pose names can be dizzying. What one teacher calls a Resting Frog another teacher introduces as Lazy Lizard. It can seems like every time you attend class, you learn a new name.

This might lead one to wonder, can anyone invent a yin yoga pose and give it whatever name they want?

Pretty much.

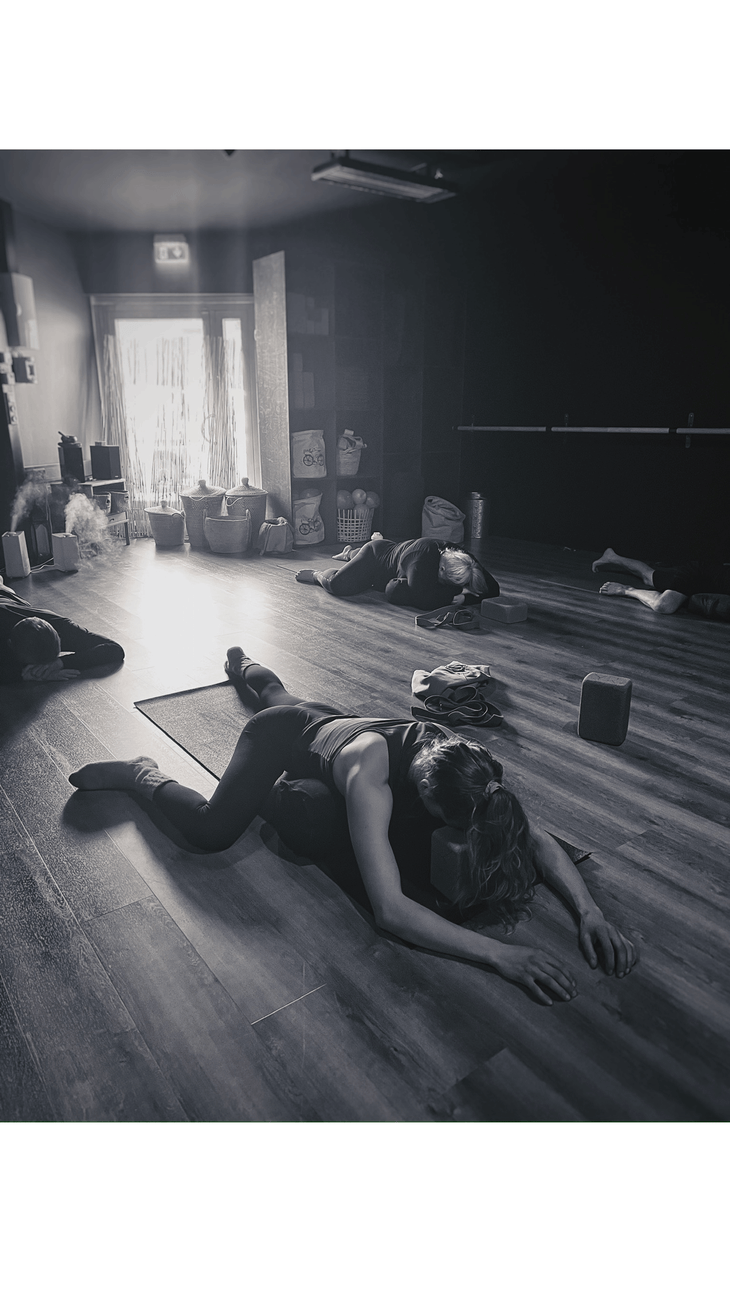

In a sense, when you’re practicing yin, you’re co-creating the pose. The teacher will help guide you to find the posture, but ultimately you’re the only person experiencing your body—the only one who truly knows where, and to what degree, you’re experiencing the sensation. Is it tolerable? Is it something you can sit with for a while? Or is there a sharp ache in your knee rather than the intended target of your hip?

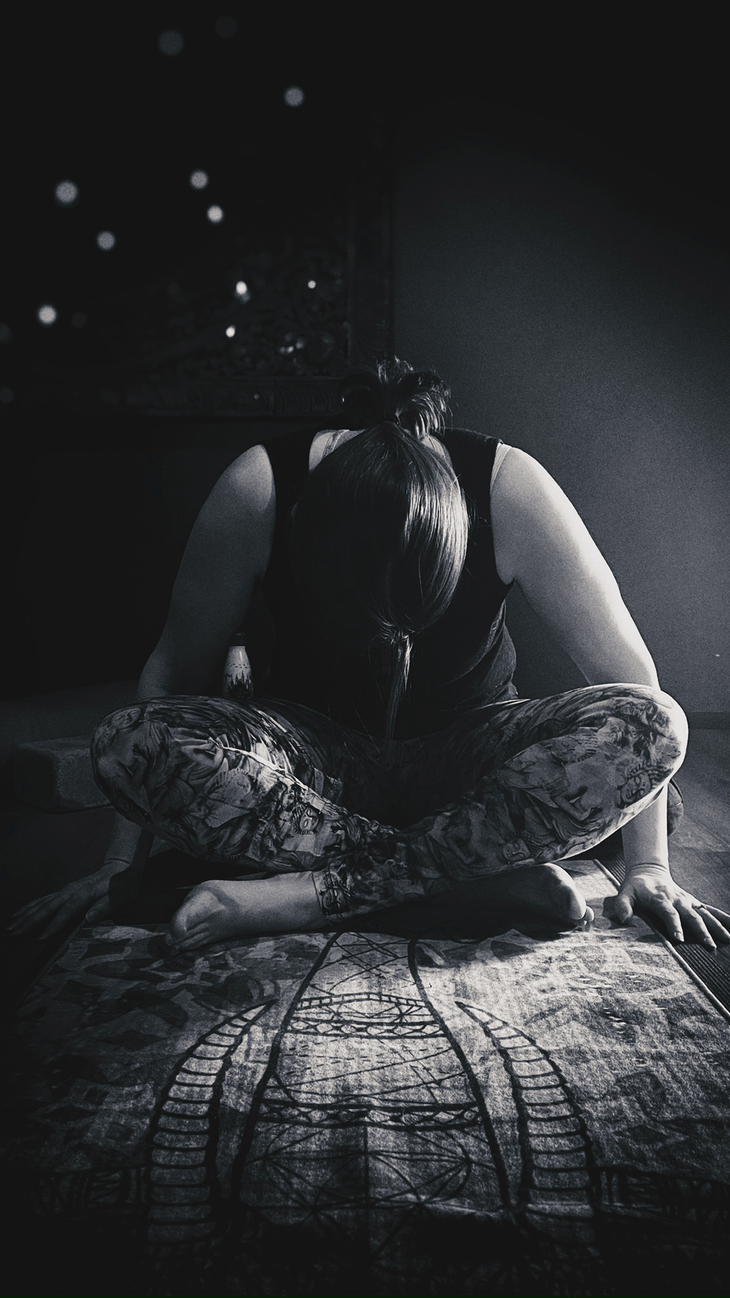

Yin invites you to engage with these questions. How does it feel? What is my body telling me? Does adjusting the shape better allow me to soften and lean in? In this way, yin increases our capacity to sense, feel, and meet ourselves. The external shape becomes a container for the act of internal quiet and profound listening.

That means there is no single alignment that is correct. There are many possible shapes, different orientations to gravity, and endless little tweaks to ensure there’s a version of each pose for every body. Because our bodies are different from one another, when you prioritize finding your perfect stretch, you will likely find yourself in a different shape than the person on the neighboring mat.

Yin yoga is a relatively newer practice, one that has gained in popularity over the last couple decades thanks in large part to yin teachers Paul and Suzee Grilley, who made a conscious decision not to use Sanskrit names. They wanted to differentiate yin postures from the traditional yoga asana, or poses, that you experience in a vinyasa class.

This decision was also made, in part, to emphasize that in yin yoga, the shape of a pose is secondary to its function. It’s not about how a pose looks, or what it’s called, but how it feels.

The yin yoga version of Pigeon Pose (Eka Pada Rajakapotasana), for example, is practiced with the intention of targeting the hip joint and gluteal region. Practitioners do not have to square their hips and try to form a 90-degree angle with their front leg for the posture to benefit. So the Grilleys chose to call this shape Sleeping Swan. Swan resembles Pigeon but is more permissive. Swan doesn’t care if you square your hips or collapse off to the side. Swan’s fine if your back leg is bent or your body is rotated. Swan simply wants you to stretch your butt and relax into a meditative space.

This continued experimentation of practicing according to our own sensations inevitably leads to the creation of new shapes—and new names. Many yin teachers, like me, are all about the silly or the literal or anything that will help students understand the shape and its underlying functional aim. The yin community’s continually evolving lexicon of names is simply evidence of that. Resting Half Frog. Cobbler. Broken Wing.

Nearly two decades into this practice, I’m still discovering this revelation through my own body and by learning from my students. This is what happens when there’s freedom to explore every possible shape.

So the next time you’re practicing a yin yoga pose and, in an effort to locate just the right sensation, you find yourself morphing from a Mermaid into something that strikes you as more of a Side-Lying Sloth, know that you’re doing it exactly right.