Published October 21, 2025 08:37AM

Throughout America’s obsession with yoga the last half century, our perception and interpretation of it has changed considerably with each decade. Take the 1980s, when the teachings were relatively unknown early in the decade. By the end of the ’80s, the practice would draw a celebrity following and become a fitness craze, but at what cost? The following article explains all that and more as part of Yoga Journal’s 50th anniversary coverage of the evolving role of yoga in America throughout the 1970s, 1980s, 1990s, 2000s, 2010s, and 2020s.

In the early 1980s, the word “yoga” was largely unknown in American culture. Whereas today there seems to be a yoga studio on every other street corner, back then, they were almost nonexistent, even in progressive places such as Berkeley, California, where I lived.

The handful of yoga communities that did exist were mostly small and self-contained. That meant before you could learn the physical practice of yoga, you needed to learn of its existence. I recall browsing in a local bookstore and being drawn to a copy of Think on These Things by the Indian spiritual writer and yoga practitioner Jiddu Krishnamurti. It was an exploration of human consciousness the likes of which I hadn’t experienced before.

That led me to another book, which led me to another, and so on, until I happened upon The Master Game: Pathways to Higher Consciousness by Robert S. de Ropp, an English biochemist who associated the new frontier of consciousness with the practice of hatha yoga. His endorsement intrigued me, even though I knew virtually nothing about yoga.

Back in the Dark Age before the internet, there were few ways to learn more about the subject, find a place to practice, or begin to understand the larger philosophy of yoga except to know someone who could teach you.

As fate would have it, a week or so after reading The Master Game, I picked up a free local newspaper, turned to the back page, and my eyes immediately fell, as if guided by unseen forces, on a modest ad for a yoga school located within easy biking distance of my apartment. I recall thinking, “Why not?”

Those of us who practiced yoga in the early ’80s existed in relative obscurity. (My father kept referring to my practice as “yogurt.”) Traveling back in time is not something, to my knowledge, that is among the powers promised by the practice, although if we could do so, we would recognize yoga in the ’80s as a younger incarnation of an old friend. The same in many ways, yet also different.

Practicing Yoga in the ’80s

Henry Ford has been quoted as saying customers could order the Ford Model T in any color they choose as long as it’s black. The same can be said about yoga in Berkeley during the 1980s in that you could have any style as long as it was Iyengar yoga. It wasn’t the hatha style I had read about, but it’s what was available.

My first yoga class was taught by Donald Moyer at the Yoga Room, an institution that he founded in 1978. He talked incessantly about his teacher, an Indian yoga master named B.K.S. Iyengar who had taught yoga to Krishnamurti. After Iyengar traveled to the US to teach in 1956 and in subsequent years, his approach to yoga started to take hold.

Classes in those days were at least 90 minutes long and two hours wasn’t unusual. They were organized by levels—1-2 for beginners and 3-4 for intermediate students. (Yes, there were “advanced” classes, although these were taught only at what was then known as the Iyengar Institute in Pune, India.)

Back in Berkeley, men typically wore their oldest and shabbiest T-shirts and shorts while women wore tights and leotards, usually in muted solid colors. We were still several years away from high-end yoga attire embellished with leopard print or pertinent reminders such as “BREATHE!”

Taking an Iyengar yoga class was, and still is, serious business. The style is unwaveringly insistent on “proper” alignment, and back then, the instruction was—how shall I say this?—physically and mentally challenging. It wouldn’t have been uncommon to hear a teacher say, “Hey, move that little toe more to the right.”

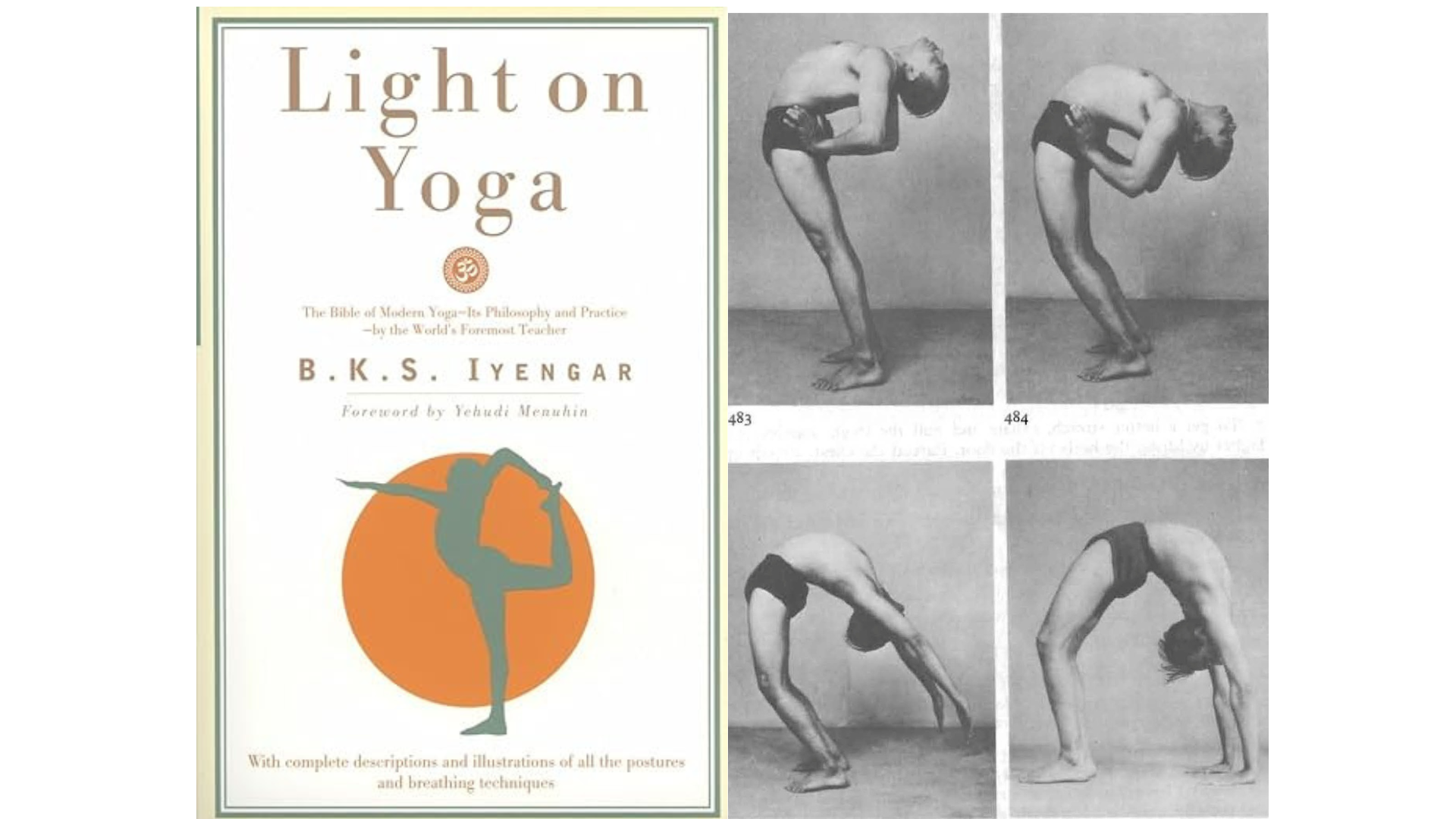

On the one hand, alignment was supposed to make the poses safer and more effective. On the other hand, teachers tended to mold students into the idealized shapes of the poses based on Iyengar’s first book, Light on Yoga, with its distinctive silver and orange cover. It was considered the definitive text for any well-rounded yoga practice in the ’80s.

The photos in the book, some 600 in all, initially struck me as unique. It had never crossed my mind that a human being could bend over backward and hold their ankles. For many students, this situation—and the resulting attempts at the pose—caused a considerable deal of pain and frustration. Today, we know perfection is impossible in yoga as well as in life. But this was decades before the concept of “accessible yoga.”

By olden time standards, contemporary yoga teachers have pretty fluid boundaries between them and their students, whereas teachers back in the ’80s were discouraged from socializing with students and were never to praise them. It was believed to be bad for the students’ ego to be so recognized. I remember the one time my teacher said a kind word to me. He did it by whispering in my ear, and on the very next pose, ripped me apart for all the class to enjoy, I mean, to educate.

Yoga Props Then and Now

When compared to what we use today, the props of old might be thought of as primitive precursors.

What passed as yoga mats in the ’80s was in sharp contrast to today’s indestructible models that are designed to last a lifetime—with price tags to match. We practiced on rectangles cut from a flimsy green material not unlike foam carpet underlay. After a few weeks of use, the material began to shred and scatter little green flecks all over the floor—especially after classes in the more intense Ashtanga style of yoga, with its jump backs and jump throughs.

As it was customary for studios to supply the “mats,” we would use one during class and then put it back in the closet afterward. I don’t remember if it ever occurred to anyone that they might need to be cleaned. It never did to me.

The other props were de rigueur or, in plain English, we used lots of them to find that elusive “proper alignment.” You could tell you were in a good class if, at the end of each session, the room looked like unruly children had flung their toys mindlessly this way and that. The most important of these props were what I think of as the Three B’s: blocks, belts, and blankets.

Blocks were chunks of wood that had been sawed without beveled edges. Although the foam, bamboo, and cork blocks of today aren’t always pleasant to lean back on, the experience isn’t terrible. But back then, when the teacher said, okay, lie over a block, no one rushed to do so. In true Iyengar fashion, we were told the painful experience was “good” for us. “Remember, the pain is in you, not in the block,” we were told. And if you happened to drop a wooden block on your foot, it hurt!

Next, straps. Today they’re available in different colors and lengths to accommodate different reach and flexibility. But in the 1980s, they were white, a little less than an inch wide, six feet long, and imported from India. When we bound ourselves in various poses, the narrowness of the strap tended to cut into our flesh, which was a nice accompaniment to lying on a roughly cut block. Again, we were told tolerating such discomfort helped us become better yogis.

But the blankets, ah, the blankets. Most blankets today are some kind of blend of cotton. But the original blankets were 100 percent wool, extraordinarily heavy in comparison to today, and rumored to be “Spanish army blankets,” though I’m unclear as to why. I still have three of these in my practice room. If you have one of these blankets, keep it under lock and key, as the last one I saw on sale was going for $40.

In Iyengar classes, no one was allowed to perform Shoulderstand without a thick blanket support folded just so. Under the influence of a teacher named Judith Lasater, blanket thickness grew to dizzying heights. Five stacked were not uncommon. The Iyengar Yoga Institute (IYI) in San Francisco looked like a blanket warehouse.

Yoga’s Proliferation in the ’80s

The practice wasn’t entirely new in the US in the 1980s. There was a long but little-known history dating back to the late 1800s. More recently, Richard Hittleman began teaching yoga on TV in 1961 and Lilias Folan launched her popular PBS program in 1972. But you had to be in front of your TV when the show was scheduled to run if you wanted instruction, which wasn’t exactly convenient.

That changed with the proliferation of VHS or video cassettes. (Remember those?) This freed us to watch anything at any time of the day or night. A yoga practice could be recorded on video, played on a VCR, and viewed on a TV. One of the first of these at-home practices was Patricia Walden’s Yoga for Beginners, produced in 1989. This was, of course, decades before YouTube and yoga apps that delivered an ever-changing array of practices.

As the popularity of these recorded classes eventually spread, so did curiosity about this thing called yoga. These teachers drew an increasingly larger audience, which eventually contributed to the birth of “yoga superstars,” pre-Internet, pre-influencer yoga teachers who would draw large in-person followings in later decades.

But there were two problems with video instruction. One, doing the same sequence over and over became boring. And two, practicing with a TV didn’t allow for physical adjustments or contact with like-minded people.

So yoga studios began to increase in number. And so did the styles of yoga being taught. In the San Francisco area alone, Walt and Magana Baptiste had been teaching yoga since they opened the first yoga school in the 1950s. Also, Larry Schultz had become known as the “bad boy of Ashtanga” for teaching a more accessible form of the practice and not forcing students to wait to “master” one pose prior to learning another as was traditional.

By the end of the decade, Yogi Bhajan had initiated a Kundalini yoga movement and Bikram Choudhury had established a hot style of yoga in Los Angeles. The flagship location of YogaWorks also opened in Santa Monica. Meanwhile, in Manhattan, teachers Sharon Gannon and David Life had founded Jivamukti Yoga Center in the East Village.

As the styles and influence of yoga grew, so did the number of students who wanted to become teachers.

Yoga Teacher Training in the 1980s

At some point relatively early in my yoga practice, I learned that several of my teachers, including Moyer, had made the 8,150-mile trek to Pune, India, to study with Iyengar in person. At the time, this seemed totally incomprehensible to me. Travel to India? To take a yoga class?

Yet after 18 months of practicing, I began to understand why someone might do something like that. And somehow I got it into my head that maybe I could become a teacher.

These days, it’s almost commonplace to enroll in a teacher training when almost every yoga studio will sell you 200 hours of coursework over three to six months in exchange for a certificate. Voila! A brand-new teacher. At least on paper. But in 1981, the training at the IYI across the bay in San Francisco lasted two years. That’s if you finished all your courses on schedule. It was a commitment as well as a gamble.

Around this time a serious controversy arose in the Iyengar community as to whether yoga teachers should be certified. One faction was both horrified and amused. Certify a yoga teacher? That went against centuries of yoga tradition in which knowledge was passed down through one-on-one training and the master teacher discerned whether a student was qualified to teach. There was talk of Patanjali spinning in his grave.

The other faction, which eventually won out, insisted that if teachers were to be taken seriously, they must be held to certain strict standards, similar to doctors and attorneys. So any individual wanting to teach with Iyengar approval–which back then was a big deal–they would need to complete a teacher training program.

Still, becoming a certified yoga teacher was a hit-or-miss proposition in terms of finding work. Even if you landed classes, there was no promise of making a livable income. I’m told the same remains true today.

After much deliberation, I decided to do it. The curriculum was focused on increasingly difficult levels of asana (poses), pranayama (breathwork), meditation, and philosophy. We were expected to write papers on each of these subjects as well as anatomy, physiology, kinesiology, manually adjusting students, and “seeing” their bodies. We were graded on each paper. Graded!

We also had to pass every single test to be approved by the IYI as a teacher. Failure to attain a passing grade resulted in being told to start all over again before you could stand in front of a class and lead students through their practice.

I passed. Then one day I was talking to fellow grad Rodney Yee when he blurted out, “Let’s open a yoga studio.” I looked at him and asked, “Are you crazy? You can’t be serious.” But he was serious and we did. After we opened the Piedmont Yoga Studio (PYS) in Oakland in 1987, we experienced firsthand the popularization of yoga that was yet to come.

Losing India’s Soul?

In 1976, a Gallup poll indicated that three percent of the US population practiced yoga. Recent surveys place the percentage closer to 16 percent.

It’s an industry that has brought tools for self-awareness, emotional regulation, and physical strength and flexibility to millions. Yet the popularization of yoga exploited the ancient practice in several ways. I vividly remember flying home after teaching somewhere and seeing an ad in the airline’s magazine for a perfume named after the Sanskrit word samsara, meaning “wandering through.” Those who strictly follow Patanjali’s teachings dedicate their lives to escape the cycle of reincarnation and samsara, which they think of as a source of unremitting existential suffering. I wrote to the company that manufactured the scent and tried to explain that this name wasn’t in their best interest. They never responded.

I could provide many such examples of what later came to be known as appropriation and what many who understood yoga considered to be disrespect. Probably the most offensive was a doormat imprinted with an om symbol. It invited you to wipe your feet on India’s soul.

Despite the increased awareness around some aspects of yoga, many of us who began practicing in the ’80s remained largely uninformed about yoga’s tradition and the fact that it encompasses a spiritual as well as a physical practice dating back more than 2,400 years. We were unaware that what we were practicing was an Americanized and modernized version of yoga.

In the relative vacuum of information that was the ’80s, another source of information was Yoga Journal. The print magazine was just five years of age when I started practicing, yet it had given voice to some of the most significant teachers of modern yoga. My involvement with it began with my writing a modest review of a video tape that instructed you on how to do yoga on an airplane. I became a contributing editor and, eventually, part of the magazine’s board of directors. Although the print magazine is no more, some of the earliest articles are still available online. It’s a window into the practice and teaching that defined the yoga scene at the time.

We can look back and recognize elements of the practice today, yet no one could have imagined then the extent to which yoga would permeate society, and even more surprisingly, how society would imprint on yoga.