A lesson in letting go of rigidity—in body and mind.

(Photo: Alexandra Iakovleva | Getty)

Published November 18, 2025 11:13AM

In Yoga Journal’s Archives series, we share a curated collection of articles originally published in past issues beginning in 1975. These stories offer a glimpse into how yoga was interpreted, written about, and practiced throughout the years. This article first appeared in the March-April 1980 issue of Yoga Journal. Find more of our Archives here.

I will never forget my striking initial reactions to Utthita Parsvakonasana (Extended Side Angle Pose or Lateral Angle Pose), one of the most beautiful and strongest of the standing poses, developed by B.K.S. lyengar. The first time I tried the pose I could not believe the difficulty it presented. Holding the right angle of the front leg exactly at 90 degrees without bending the back leg, and keeping the front knee exactly over the foot, seemed impossible, and I was exhausted by the attempt.

With the wisdom of hindsight, I now know that Parsvakonasana challenged the lack of strength in my legs in my overall hatha yoga practice, as well as my ability to maintain an asana or persevere in a difficult task.

Common Challenges in Extended Side Angle Pose

Generally, all the standing poses are of benefit to the lower extremities—especially the hip joints, the knee joints, the ankles, and feet. In particular, this pose tends to stretch the inner thighs, the adductor muscles, as well as the ligaments of the inner hip joint. This area tends to be tight in Western students because of chair-sitting, which keeps the legs relatively close together. This tightness is significant for two reasons.

Knee and Hip Restrictions

First, it must be remembered that movement in one part of the body reflects the total movements of all the joints in that area. The movement at the hip joint, for example, affects and is affected by movement at the knee as well as the joint above—the sacroiliac joint at the junction of the sacrum with the pelvis. If the hip joint is restricted to just one plane of movement, and is thus not functioning properly, the knee cannot work well either. The dysfunction may be minor, but years of minor misuse can lead to major problems such as contributing to the development of degenerative changes within the joint. As an analogy, if a car is out of alignment, the tires are worn unevenly and must be replaced. In the body, if a joint is tight it tends to wear unevenly. I believe this contributes over time to degenerative problems. Therefore, it is important to keep the joint free in all planes of movement, even in difficult poses that require the openness of Utthita Parsvakonasana.

Emotional Obstacles

The second significant aspect of this tightness of the inner thighs and hip joints concerns the psychological effects of the pose. Since this pose represents a perfect balance of strength and openness, a discussion of strength and rigidity is apropos. Too often rigidity is mistaken for strength; one may feel weak inside and therefore create an outer rigidity or tightness that gives a false feeling of strength.

But freedom comes from having the inner strength necessary to let go of the outer rigidity without the accompanying fear of weakness. Yoga teaches that outer softness is not weakness, just as there is strength in the flexibility of the willow tree. But at the other end of the continuum, one must not mistake flexibility for inner strength. There must be a balance between strength and flexibility, between the inner and the outer, between surrendering and resisting, in order for one to practice in the true spirit of yoga. And this is how the practice of asana represents the spiritual essence of yoga.

Detaching From the Ego

Utthita Parsvakonasana has taught me a lot about the deeper meaning of yoga. My first introduction to it was accompanied by strong feelings of dislike which were related to the discomfort the pose created. Gradually, after years of practice, I began to enjoy the pose. The stretch began to feel familiar, and as the pose seemed to improve, my ego became attached to my improved execution of the pose. With more practice, even this is beginning to change. Now I have a more neutral attitude about the pose, even though I practice it everyday.

This series of reactions parallels our reactions to life which Patanjali discusses in his Yoga Sutras. Often tasks seem difficult and unpleasant; their accomplishment impossible. However, the ego can also become attached to the pleasure of improving—a big trap for the practitioners of yoga. But attachment, whether to pleasure or pain, is the same as far as its power to interfere with the freedom of the self. Without detachment from the ego, the inner self will never be able to shine forth in freedom. This is why one must surrender in one’s practice, surrender into the stretch. Giving up the protection that tightness and rigidity offer parallels to giving up the attachment of the ego, whether it is to the image of oneself as a sufferer or as an experiencer of pleasure.

According to Patanjali, we must let go of both attachments in order for dynamic tranquility to express itself through the individual. For most of us, the real challenge does not come from letting go of an attachment to pain, but rather in letting go of our attachment to progress, to accomplishment, and to improvement. Here is where the real challenge of yoga lies.

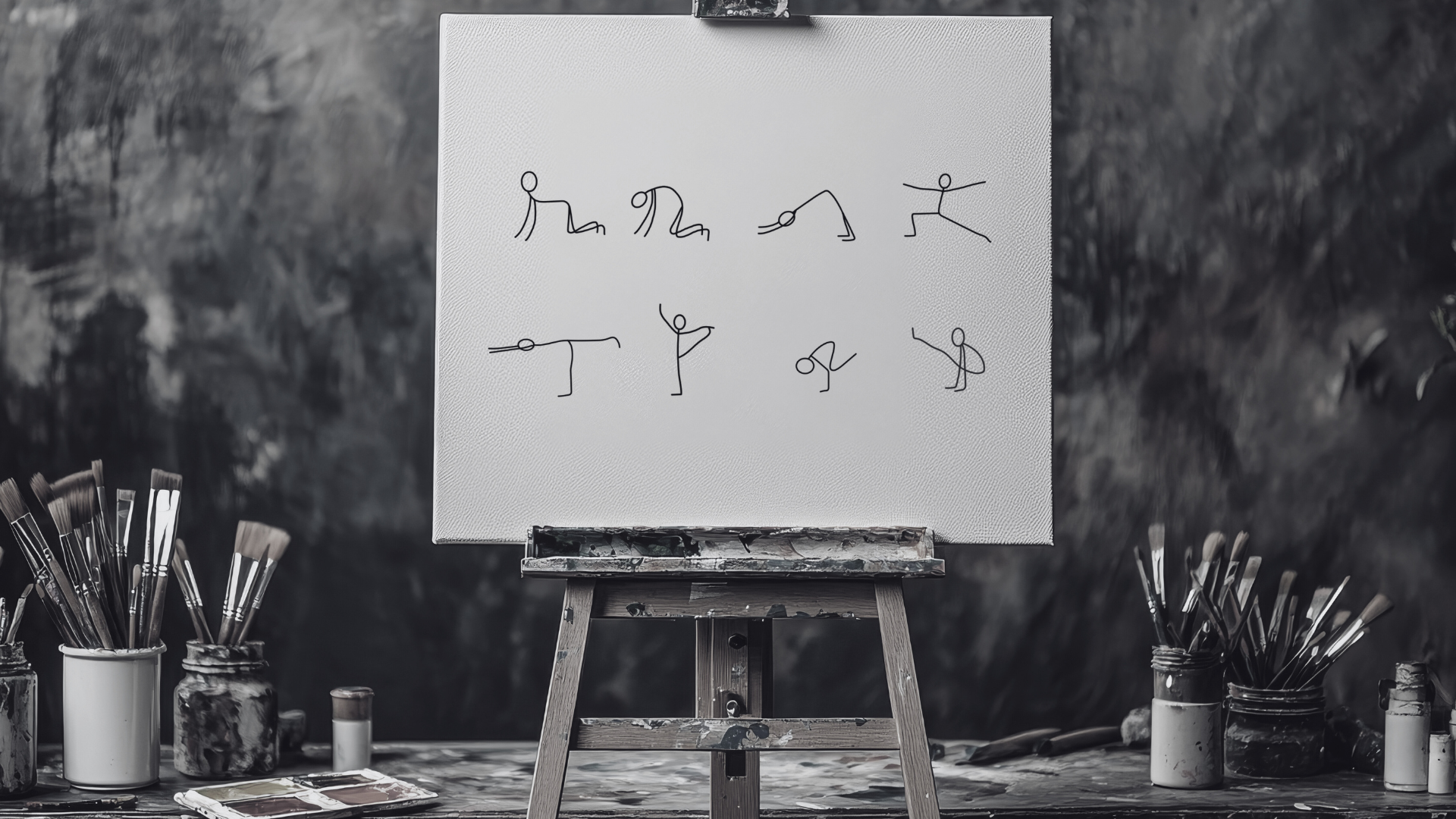

How to Practice Utthita Parsvakonasana

To practice Utthita Parsvakonasana correctly, assume a wide stance with the feet pointing forward, and the pelvis tucked. The leading foot is then turned out 90 degrees and the back foot is turned in 30 degrees. Now, bend the leading knee until the leg achieves a right angle. Remember, only the knee moves, the trunk faces forward . Extend the arm down at the outside of the knee, and rest the fingers on the floor. Care should be taken not to allow the right angle to widen as the hand is being taken down. The breath should be coordinated with the movement so that all movement occurs on the exhalation. Repeat the pose on the other side.

There are two aids for the pose which can be especially effective for helping work out tight hips. A folded blanket placed behind the foot for the hand to rest on keeps the student from descending too far into the pose and thus more attention can be focused on keeping the back hip open, preventing it from rolling forward.

Another effective aid is to place the arm in front of the knee. This helps the student keep the front knee back as well as giving him/her a point of resistance. By pushing against the arm, and moving the pelvis forward instead of the knee, more work is felt in the front hip joint.

The author gratefully acknowledges her teacher B.K.S. lyengar, and his book Light on Yoga, in the writing of this article.