Published January 20, 2026 02:59PM

Yoga Journal’s archives series is a curated collection of articles originally published in past issues beginning in 1975. This article first appeared in the January 2002 issue of Yoga Journal.

As we work to create healthy and safe backbends—and especially as we explore deeper, more challenging backbends, like dropping back from standing into Urdhva Dhanurasana (Upward-Facing Bow Pose or Wheel Pose)—we should always seek to develop a curve of the spine that is even, with no sharp angles sticking in or out.

Many students measure their progress in backbending by how extreme they can make the curves in their backs, forcing themselves into backbends before their spines are ready. Rather than finding length and openness and developing an even, healthy curve, they jam their backs, strain their sacroiliac joints and the rest of the sacral area, and wind up with long-term or irreparable damage. Often students are impressed with a back that folds almost in half, giving the appearance of extreme flexibility, but this is the most dangerous way to bend the back.

If flexibility exists primarily in just one point of the back, that area will be very vulnerable to injury. A yoga student working with backbends is much like a carpenter working to create a curve in a fine piece of wood. Just as wood constantly overstressed in one place will eventually break, a spine overstressed in one place will eventually suffer. And just as a piece of wood breaks if we try to shape it into a curve before it is ready, we can harm the back if we try to bend it before warming it up and making it supple.

Of course, there are certain spines that, like certain pieces of wood, are remarkably flexible. Like every piece of wood, every spine can bend, but the degree of flexibility will vary. In yoga, we work to maximize the usefulness of the unique body we are given, just as a master carpenter seeks to work with the grain of each individual piece of wood. And we need to remember that our spine differs from a piece of wood in one critical way: If we over-stress it, we can’t replace it.

Coming into Wheel Pose From the Mat

To work safely on dropping back from standing into Urdhva Dhanurasana, it’s important to first learn proper actions as you practice coming into Urdhva Dhanurasana from the floor. Begin by lying on your back with your knees bent and feet on the floor, heels directly in line with and a few inches in front of the sitting bones.

Bring the outer edges of the feet parallel and press all four corners of each foot down evenly. Lift the arches as well as the inner and outer ankles. For most people, the knees tend to splay out farther than hip distance. To counteract this, roll the outer thighs toward the inner thighs and release the inner thighs toward the floor until the thighs are parallel. A common mistake is to squeeze the knees together to make the thighs parallel, but if you work in this way, you risk over-rotating and straining the inner knees.

Proper work in the legs and buttocks is absolutely essential to protect the lower back in backbends. Students frequently injure themselves in backbending because they compress the lumbar spine by clenching the glutes maximus, one of the muscles responsible for external rotation of the legs. Squeezing and rotating the buttocks too tightly together pinches the lower back.

Instead, lengthen the buttocks flesh away from the lumbar spine in the direction of the knees. At the same time, draw the hamstrings up toward the buttocks and broaden the backs of the thighs. Understanding these actions is critical to creating length, stability, and safety in the back.

When you have properly engaged your legs lying on your back with knees bent, bend your elbows and place your palms on the floor close to the shoulders, with the fingers pointing toward the feet. Set the hands shoulder-width apart.

Use Your Breath

Bring your attention to the breath and let it be soft and even, with each inhalation as long as each exhalation. On an inhalation, press into your hands and feet and come up onto the top of your head (Figure 1). Move your feet if necessary to align the knees directly over the ankles, making sure you keep the feet at hip width.

Be light on your head; most of your upper body weight should be on your arms. Draw the elbows toward each other until they are shoulder-width apart. If necessary, adjust the hands until they are directly under the elbows with the creases of the wrists parallel to the wall.

Play with your hand placement to discover which finger (index or middle) needs to point straight forward in order for your weight to be distributed evenly between the inner and outer wrists. Press all the knuckles of your fingers evenly into the ground; you’ll probably need to emphasize pressing the knuckles of your index fingers, as the weight often rolls to the outer hand.

Now lift the shoulders up toward the ceiling, drawing them away from your ears. Attempt to create a right angle between your hand and forearm at the wrist and another right angle between the forearm and upper arm at the elbow.

Don’t be discouraged. With a little time, you will gain flexibility and be able to extend the arms more fully.

As your elbows line up over your wrists and your shoulders move away from the floor, draw your forearms toward your knees. This isometric action helps properly seat the heads of the upper arm bones in the shoulder sockets. When the shoulders are secured in this way, move your thoracic spine and the bottom tips of your shoulder blades toward your chest.

Working all these actions, with bent arms and head on the ground, opens the chest safely before you go up into full Urdhva Dhanurasana. As you continue to work in this position, strongly reinforce the actions needed to keep your thighs parallel and your lower back long. As you move your buttocks flesh toward the backs of your knees, also draw your shinbones back into your calf muscles and press your calves down into your heels. These actions all work to open the groin.

Safety Tips in Wheel Pose

As you come up into full Urdhva Dhanurasana, it is important that the elbows not splay out past shoulder width. If the elbows splay, your inner and outer arms will not work evenly, and you run the risk of misaligning the upper arm bone in the shoulder socket and straining your wrists, elbows, and shoulders.

If your elbows tend to splay, create a shoulder-width loop with a yoga strap and place it just above your elbows. If you are stiff, you may not be able to straighten your arms fully with the belt on. Don’t be discouraged. It’s OK to keep your elbows slightly bent. With time you will gain flexibility and be able to extend the arms.

In the Urdhva Dhanurasana prep position, it was safe to open the chest toward the wall as much as you could; with the elbows bent, you could not “puff your armpits,” pressing the head of each upper arm bone toward the skin. But as you straighten the arms, it is very common for the armpits to puff. This is not only dangerous over time for the shoulder joint, it also allows you to avoid opening and working the chest and shoulders where they are stiff and weak.

Instead of creating proper opening, puffing the armpit merely shifts weight into the most flexible and vulnerable part of the joint. To avoid this when you move from the prep position into the full pose, don’t press the chest toward the wall; instead, lift the shoulder blades straight up toward the ceiling.

It is true that in an ideal Urdhva Dhanurasana the elbows and shoulders stack directly over the wrists. But this alignment must be achieved by properly opening the shoulders, chest, and spine, not by pushing your upper arms bones out of the shoulder sockets.

It is critical in backbending to keep the breath free. If you hold your breath, you tighten the body and mind. The mind must remain soft so you can listen to the messages of your body.

Now let’s apply these alignment principles in Urdhva Dhanurasana. With an inhalation, come up to the Urdhva Dhanurasana Prep. Secure your upper arms in your shoulder sockets and open your chest fully. Keep your feet parallel and work to rotate your thighs until they are parallel. With your next inhalation, slowly begin to lift up into Urdhva Dhanurasana (Figure 2).

As you straighten the arms, remember to keep the chest from moving forward; instead, lift straight up. If the elbows splay as you come up, come down and place a strap just above your elbows.Now that you’re up, relax your neck so that your ears are alongside your upper arms and practice breathing smoothly.

Keeping your hands firmly rooted, spin your outer arms toward your inner arms, and move your forearms toward each other as you fully straighten your elbows. Make your outer upper arms firm and draw them toward the bones. Again without moving your chest forward, create maximum extension from the hands to the shoulder blades.

Lift your shoulders and chest straight up toward the ceiling, creating as much height as possible. Without losing any elevation and without puffing your armpits at all, challenge your back ribs to move farther into your body. Now go back to the work in your legs.

Keeping your knees directly over your ankles, press down into your feet. Lift your outer hips and soften your inner thighs toward the ground. The work of the inner thighs is subtle and difficult to find, but without this work your groins will be hard and puffed toward the ceiling, and the whole sacral area, especially the sacroiliac joints, will be compressed.

After softening your inner thighs down, slide the flesh of your buttocks toward the backs of your knees and firm the backs of the thighs. All these leg and buttock actions, coupled with the movement of the back ribs into the body, will lengthen the curve along the back of the body. The backbend in this pose should be made deeper by creating height evenly.

The navel should be the peak of your pose; from your hands and your feet, your body should feel as though it rises symmetrically. A common mistake in this pose is to straighten the legs and shift your weight toward your hands to create more sensation of stretch in the chest. This action does not actually create height; as you shift the weight, you lose the work of the buttocks flesh toward the knees, collapse the groins, and usually compress the lower back.

Another mistake is to break the smooth curve of the front of your body by poking your front ribs out. The back side of your body should form a smooth curve, with no sudden angles.

Coming into Wheel Pose Using a Wall

Once you’re fairly comfortable with Urdhva Dhanurasana, you can work on dropping back into it from standing.

To drop back into Urdhva Dhanurasana without harming your lower back, you must be solid in your leg work and you also need to be able to create a deep enough curve in your upper back. If your feet and thighs do not work properly, your lower back will bear too much of the brunt of the backbend. If you can’t lift and open the chest and upper back enough, you also force too much of the curve into the lower back.

Back pain is always a warning message from the body.

Do not fool yourself: Back pain won’t go away if you keep repeating backbends that strain your lower back. If you feel pain in your lower back, go back to practicing Urdhva Dhanurasana from the floor or even Urdhva Dhanurasana prep.

To begin your work with drop-backs, place your mat perpendicular to a wall and stand facing away from it. Make a loop in a yoga belt, place it around both legs at the middle of your thighs, and then tighten the belt to hip-width so your thighs can’t splay apart.

Also put a block between your feet to help you keep them hip-width apart and parallel. Just as a carpenter secures wood with clamps to direct the bend where he wants it to go, you can create clamps with your muscles to keep your body safe as it opens.

At the base of this pose, you create one clamp by bracing the shins back into the calf muscles. If this clamp is lost and the shins move forward, you’ll lose lift in your groins. Farther up the legs, you will create a second clamp by pressing the front thighs back into the hamstrings. If you release either of these clamps, you risk strain to your lower back.

Place the palms of your hands together in prayer position at the center of your chest, with the knuckles of your thumbs placed at the bottom of your sternum and your fingers together and pointing up at about 45 degrees. Gaze down gently at your fingertips and breathe freely Practice Samasthiti (Equal Standing Pose).

Press down into the four corners of each foot and lift your arches and ankles. Create a straight line of energy from your heels into your sitting bones. If you push the sitting bones forward, you create a tuck in the pelvis and lose the alignment of Samasthiti: You break the heel-to-sit-ting-bone connection, puff your groins forward, and compress your sacral area and lower back.

Instead, strongly and evenly lift the outer thighs, the inner thighs, and front and back of your thighs. As you move the tops of your thighs back, release the buttocks flesh toward your heels. Now lift your frontal hip bones up away from your thighs. Visualize your entire pelvis lifting up and out of your legs. 4

Now draw your chest up away from your pelvis. Even as you lift your chest, soften the front ribs down toward the frontal hip bones. If you create too much space between the hip bones and front ribs, the curve at the back of your body will compress at your lumbar spine. You must have both lift in the chest and softening in the lower ribs to create length in the lower back.

Drawing the waist area upward and lifting your whole torso, start to work the curve of the backbend up your back. Draw the bottom tips of the shoulder blades into your body and lift your sternum up toward the ceiling. Spread across your collarbones and drop your shoulders away from your ears. Slide the trapezius muscles down the back and into the bottom tips of the shoulder blades. Feel as though these actions create a wheel in your chest, rotating the front of your chest upward.

Without losing the work of Samasthiti in the legs, keep moving the curve of the backbend up your back. Draw your sternum away from your navel and are your gaze toward the wall behind you. Keep lifting your chest and thoracic spine up toward the ceiling to avoid sinking your weight into your lower back. When you can see the wall, extend your arms overhead and place your palms on the wall (Figure 3). Keep both hands at the same height and press them evenly into the wall.

Come out of the pose with extreme care; coming into and out of poses is where many students get hurt.

Again turn your attention to your legs. You may be pushing your thighs out into the belt. Instead, attempt to slacken the belt. At the same time, keep the backs of your thighs lifting and reaffirm the heel-to-sitting-bone connection. Along with the other leg actions of Samasthiti, this will provide a sensation that I think of as “staying high up on the legs.”

From this grounding and lifting, move your back ribs, the bottom tips of your shoulder blades, and your chest up. As in Urdhva Dhanurasana, rotate your outer arms toward your inner arms to encourage proper positioning of your upper arm bones in your shoulder sockets.

How to Release the Pose Mindfully

It’s important to come out of this pose with care; coming into and out of poses is often where students get hurt. Don’t stay until you’re exhausted. Begin by pressing your shins back into your calf muscles. This action will root your heels and deepen the lift and height in your groins.

As you lift back to vertical, you must resist leaning to one side. A common mistake in coming up is to reach up more with one hand than the other and tilt the torso to come up. This is risky for it can torque the spine. The arms must leave the wall at the same time and with equal energy.

To come up, use your inhalation to anchor your shins back, press down through your heels, move the tops of your thighs into your hamstrings, and lift your chest over the plumb line of your legs. This lift is the key to not hurting the back. Do not be in a hurry to move beyond this drop-back prep at the wall. It’s much harder than it looks, and it’s a good variation to stick with and work on for some time.

This variation is especially useful because it concentrates the backbend in your chest and upper back-for most students, the hardest areas to open. Once you become secure in your leg work and can lift your chest while staying calm and connected to the breath, it is time to work your hands down the wall. Start slowly, moving the hands down the wall a few inches at a time, always reinforcing the work of the legs and chest.

If at any point you realize you’ve lost any of this work, practice satya (truth) and ahimsa (nonviolence): Back up a little and work to recreate integrity in the curve of your backbend. With time, patience, and keeping up a regular practice, most students who follow these guidelines will be able to walk all the way down to the floor.

Coming into Wheel Pose With a Prop

When walking down the wall becomes comfortable, it’s time to take the props away and learn to drop back. This should also be done in stages; you can place a filing cabinet, chair, or footstool securely against a wall, and drop back onto that instead of going the whole way to the floor.

Many students face fear as they learn to drop back. You can move through fear, but you must also listen to it. Often the body sends intelligent warnings in the form of fear. You can misinterpret these messages as mental weaknesses and force yourself through them, but I don’t recommend this.

With practice and with the help of an experienced teacher, you can learn to tell when your body is truly not ready for something and when you have simply reached a bridge that you are afraid to cross. Without the help of a teacher, your breath is often your only guide. It will usually stop when you are scared. So if you find you cannot breathe comfortably, return to the previous variations. With a chair or other prop placed securely against a wall, stand with your feet hip-width apart and your hands in prayer position (anjali mudra). Reinvest in the work of the legs and begin to turn the wheel toward the sky.

Without the help of a teacher, your breath is often your only guide. It usually stops when you are afraid. If you can’t breathe easily, return to a previous variation.

Imagine that you’re making the shape of a candy cane with your body; your legs are the long staff and your upper body is the crook. As you arch back, look for your prop and make sure your breath is still long and even. It’s easy to stop breathing as you prepare to drop back. Move your shins back into your calves and press your calves down into your heels.

Staying high up on your legs, lift the frontal hipbones strongly: Lift up and out of the legs as you raise your chest and curve your upper back. Once you can see the prop, extend your arms overhead. Don’t allow the weight of the arms to decrease the height of the chest; if possible, lift your chest even more. Rotate your triceps in toward your biceps and extend your arms, letting them create more curve in your upper back.

Bend your knees slightly and slowly let your hands come to the prop (Figure 4). Keep your ears in line with your upper arms so you don’t compress your neck. Rotate your outer arms in toward your ears and straighten your arms. Lift the bottom tips of your shoulder blades straight up, increasing the curve in your upper back.

Soften your front ribs as you maintain the lift in the frontal hip bones. To come up, move your shins strongly back into your calves and press your calves down into your heels to maximally lengthen your groins. When you do this well, you never lose the strength of Mountain Pose (Tadasana) in your legs, and this stability allows your torso to lift right back up onto your legs.

The Full Drop-back into Wheel Pose

Practice dropping back onto a prop for some time, until coming up and down is comfortable and you feel no strain in the breath and the spine. At this point, you are ready to drop back in the center of the room. If possible, it’s best to practice this at first with a teacher, who can offer support if you need it.

Stand in Samasthiti, feet hip-width apart. Place your hands in prayer position at the center of your chest. Again create a wheel in your chest and support this wheel with the work of your legs. Once you can see the floor, reach your arms overhead, extending them fully.

Reach your arms as though they start in your legs, lengthening through the sides of your body. Keeping your weight in your heels, bend your knees slightly; slowly with control, place your hands on the ground (Figure 5). Your landing must be soft. If your elbows bend when you land or if you feel as though you’re falling a long way rather than arching back with control, you are not yet ready for dropping back to the floor. You don’t yet have enough height in your legs or enough curve in your chest.

Practice your yamas (satya and ahimsa) and go back to the previous variations. Coming back up to standing is even more difficult than dropping back to Urdhva Dhanurasana. Unless you have a teacher to spot you, I strongly recommend that you simply bring your back to the ground to come out of the pose.

The full drop-back is not appropriate for everyone. But the variations and adaptations outlined in this article can be practiced safely by most students. As yoga students we must learn moderation. If we try to move farther or faster than the body is ready for, we will suffer. Suffering occurs when we get frustrated and demand to go where we should not. When we are not sensitive, when we stop listening and grab and hold on tight to our desires, we suffer more. The Yoga Sutra calls this suffering dubkha.

Yoga is the process of removing duhkha, but this does not happen if we just mindlessly practice poses. It happens when we listen, when we are honest, and when we are not clouded by misperception. The greatest service we can do for ourselves is to honor and celebrate what we have. When we are content with this, we are practicing yoga.

How to Practice Wheel Pose

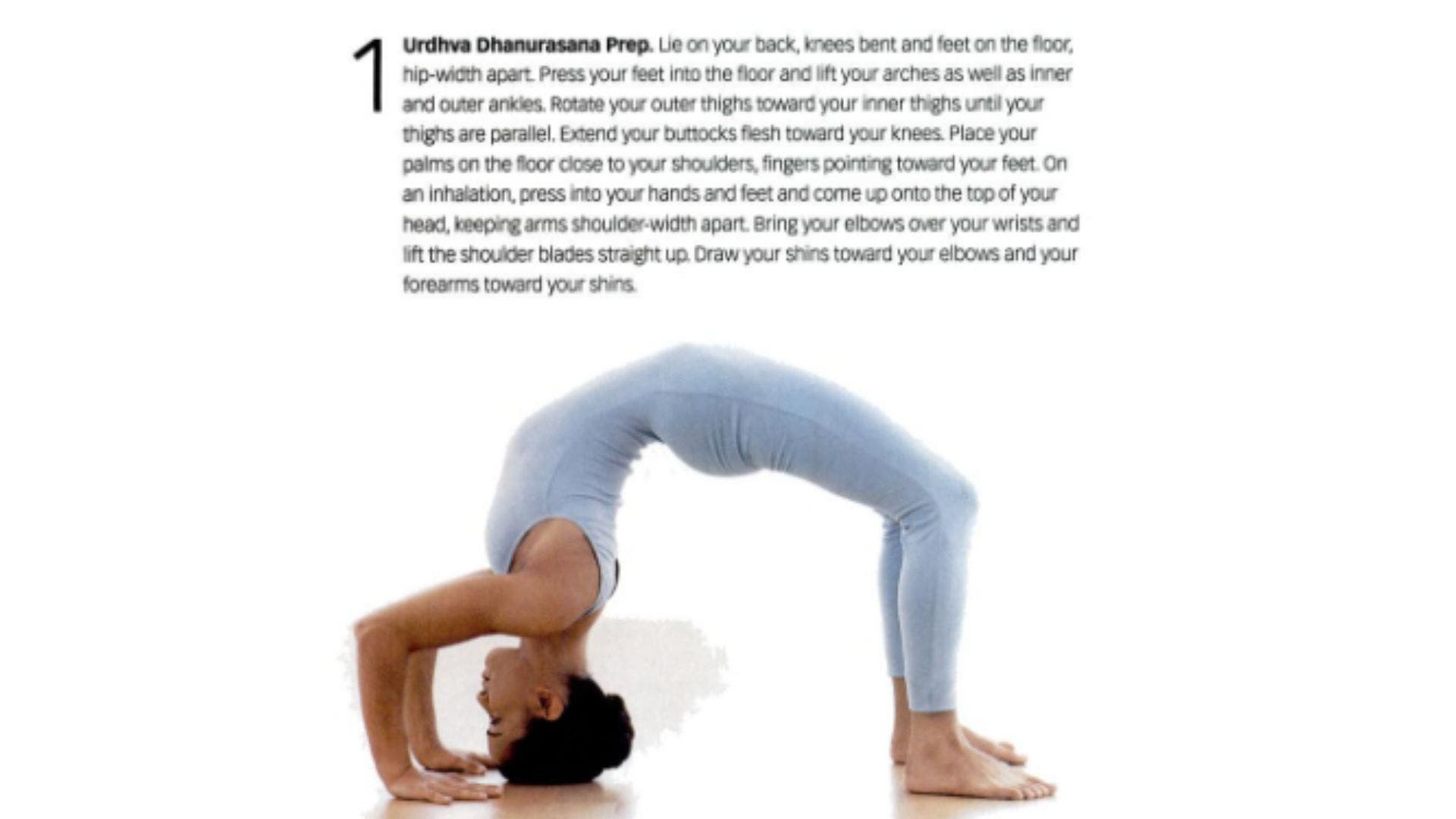

1. Urdhva Dhanurasana Prep

Lie on your back, knees bent and feet on the floor, hip-width apart. Press your feet into the floor and lift your arches as well as inner and outer ankles. Rotate your outer thighs toward your inner thighs until your thighs are parallel. Extend your buttocks flesh toward your knees. Place your palms on the floor close to your shoulders, fingers pointing toward your feet. On an inhalation, press into your hands and feet and come up onto the top of your head, keeping arms shoulder-width apart. Bring your elbows over your wrists and lift the shoulder blades straight up. Draw your shins toward your elbows and your forearms toward your shins.

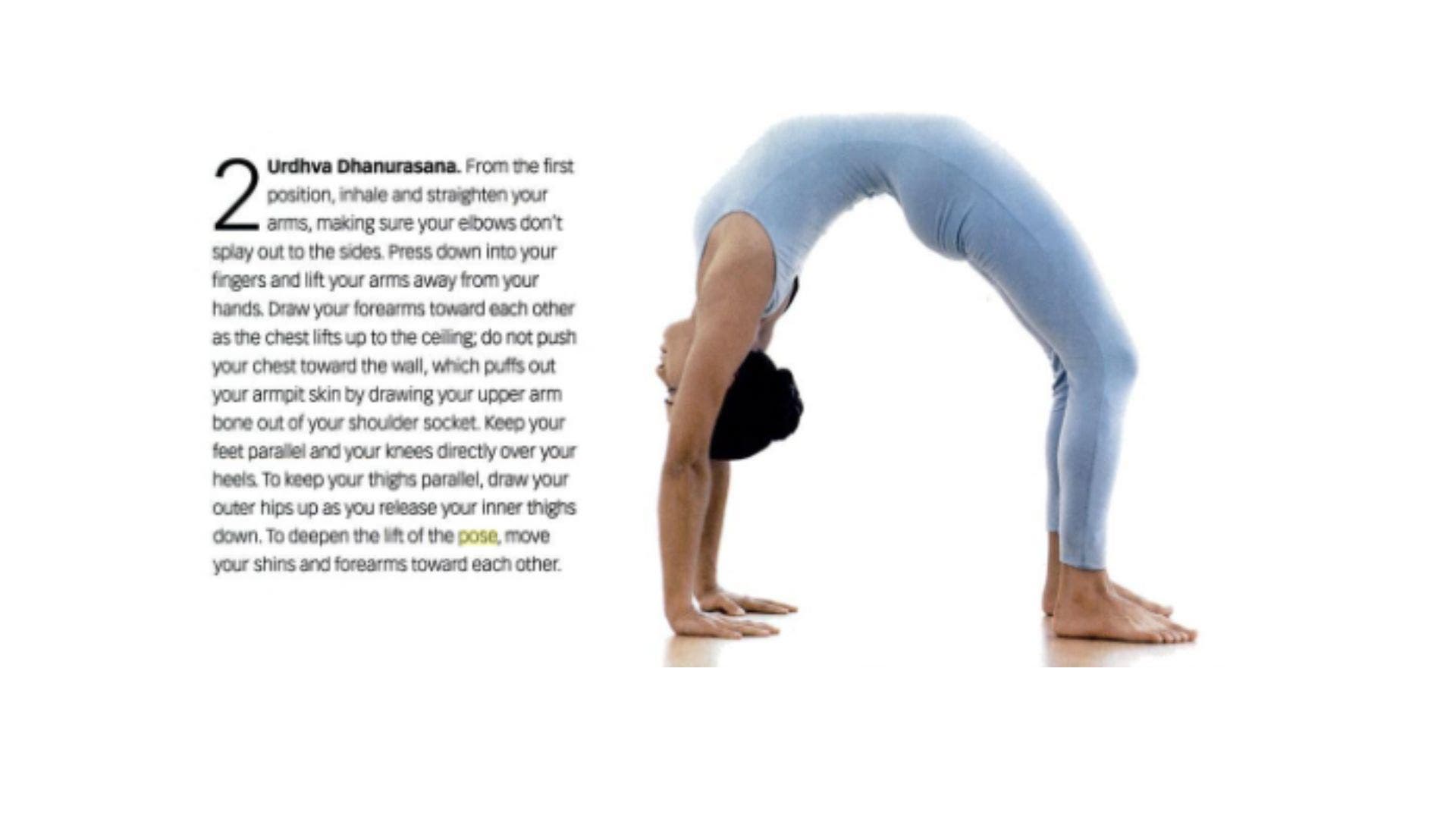

2. Urdhva Dhanurasana

From the first position, inhale and straighten your arms, making sure your elbows don’t splay out to the sides. Press down into your fingers and lift your arms away from your hands. Draw your forearms toward each other as the chest lifts up to the ceiling; do not push your chest toward the wall, which puffs out your armpit skin by drawing your upper arm bone out of your shoulder socket.

Keep your feet parallel and your knees directly over your heels. To keep your thighs parallel, draw your outer hips up as you release your inner thighs down. To deepen the lift of the pose, move your shins and forearms toward each other.

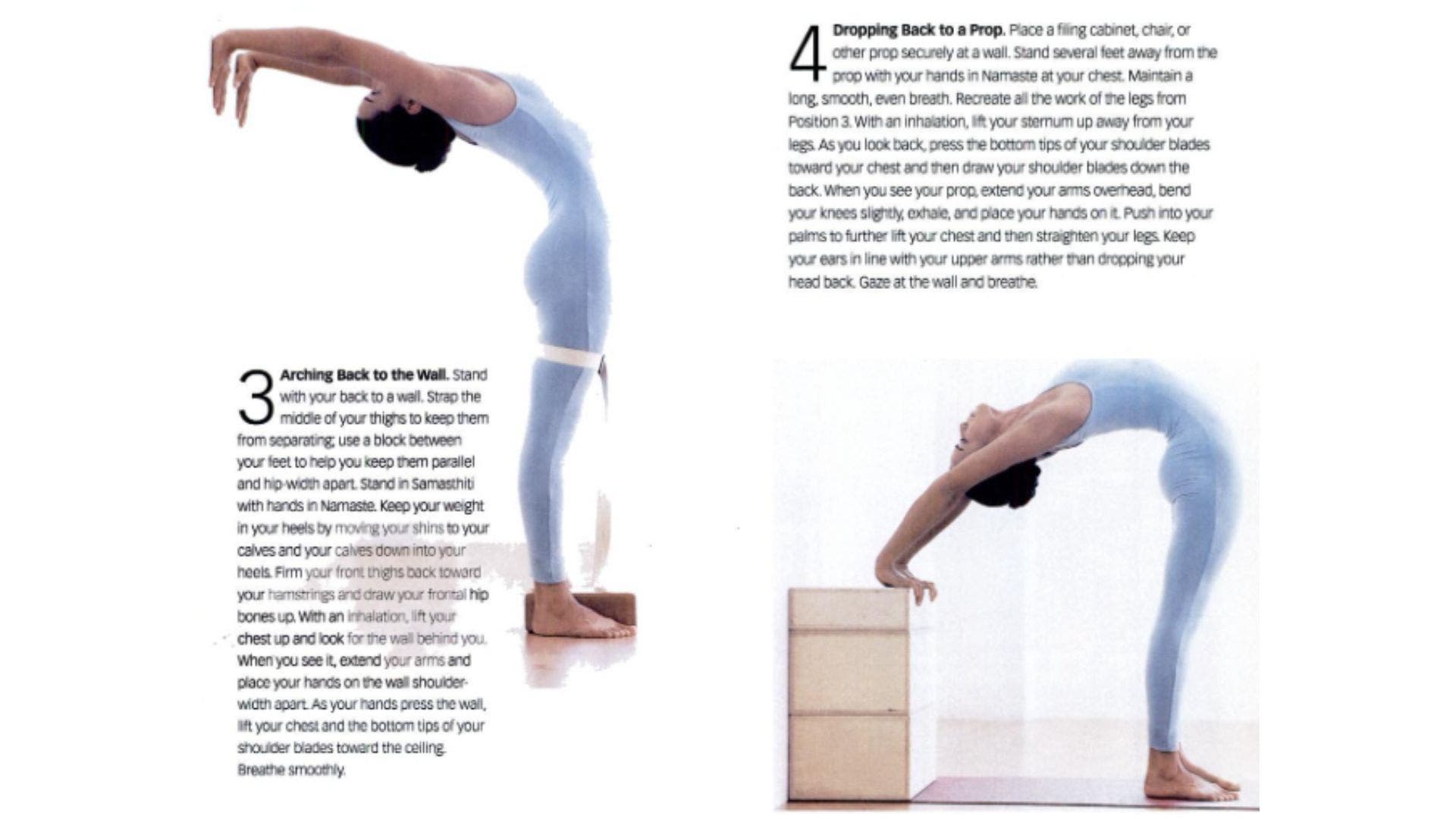

3. Arching Back to the Wall

Stand with your back to a wall. Strap the middle of your thighs to keep them from separating; use a block between your feet to help you keep them parallel and hip-width apart. Stand in Samasthiti with hands in Namaste. Keep your weight in your heels by moving your shins to your calves and your calves down into your heels.

Firm your front thighs back toward your hamstrings and draw your frontal hip bones up. With an inhalation, lift your chest up and look for the wall behind you. When you see it, extend your arms and place your hands on the wall shoulder-width apart. As your hands press the wall, lift your chest and the bottom tips of your shoulder blades toward the ceiling. Breathe smoothly.

4. Dropping Back to a Prop

Place a filing cabinet, chair, or other prop securely at a wall. stand several feet away from the prop with your hands in Namaste at your chest. Maintain a long, smooth, even breath. Recreate all the work of the legs from Position 3.

With an inhalation, lift your sternum up away from your legs. As you look back, press the bottom tips of your shoulder blades toward your chest and then draw your shoulder blades down the back. When you see your prop, extend your arms overhead, bend your knees slightly, exhale, and place your hands on it. Push into your palms to further lift your chest and then straighten your legs. Keep your ears in line with your upper arms rather than dropping your head back. Gaze at the wall and breathe.

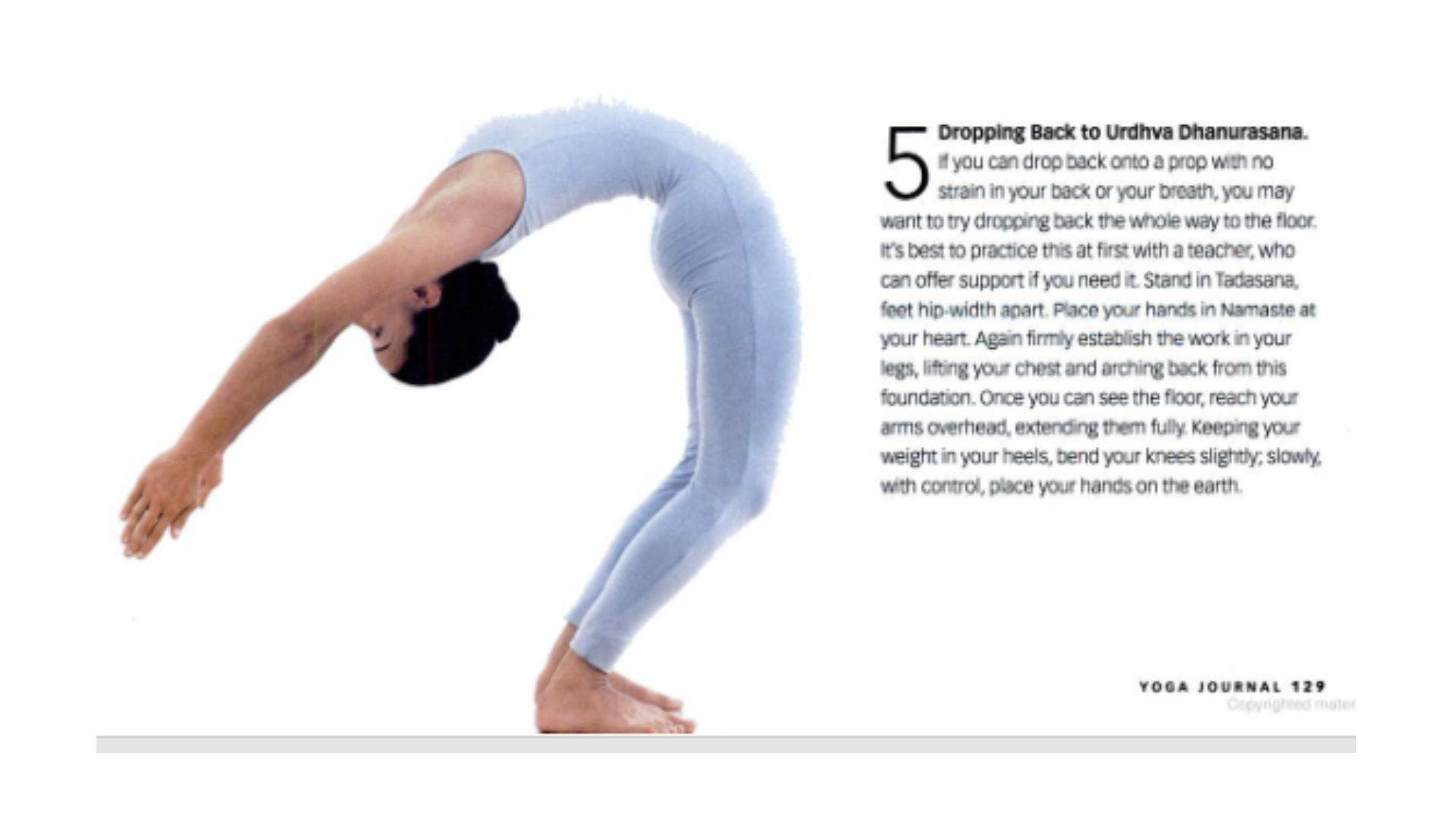

5. Dropping Back to Urdhva Dhanurasana

If you can drop back onto a prop with no strain in your back or your breath, you may want to try dropping back the whole way to the floor. It’s best to practice this at first with a teacher, who can offer support if you need it. Stand in Tadasana, feet hip-width apart.

Place your hands in Namaste at your heart. Again firmly establish the work in your legs, lifting your chest and arching back from this foundation. Once you can see the floor, reach your arms overhead, extending them fully. Keeping your weight in your heels, bend your knees slightly; slowly, with control, place your hands on the earth.