Updated February 10, 2026 06:54PM

Yoga Journal’s archives series is a curated collection of articles originally published in past issues beginning in 1975. This article first appeared in the March-April 1991 issue of Yoga Journal.

A short, iridescent creature, the peacock drags behind him an improbable array of magnificent feathers, like the long train of a bridal gown. The creature is only about 18 inches tall yet measures more than five feet in length from beak to longest tail feather. As if to prove that he is the king of birds, the peacock even wears a small crown of feathers atop his head.

The peacock isn’t shy; he doesn’t hide his splendor. He preens and struts, turning first to one side, then to the other, so all members of his audience can view him equally. When a peacock “displays,” or lifts his tail feathers to form a tall fan, a crowd will often gather, awestruck by the fact that such a creature exists.

If the peacock were timid and self-conscious, he would not appear nearly so awesome. He is not the architect of his own magnificence; he only exemplifies the creativity of the life force that moves through us all. Because we know that he is more splendid than anything we humans could create, his beauty leads us to humbly respect the creative power of life.

The vital essences of Pincha Mayurasana, or Peacock Pose, teaches us to take up our full quota of space in the world, to burst through the bonds that tie us down, to explore what is possible. Because the whole body must be activated in this pose, Pincha Mayurasana can be exhilarating. An asana that can’t be done shyly, Peacock Pose depends on upward momentum. It allows us to make the powerful statement, “I am.”

Since its very nature is assertive, Pincha Mayurasana is a good pose for the introverted or self-effacing. It teaches us to take up our full quota of space in this world. But doesn’t yoga teach us to drop the ego, not feed it? How can we simultaneously assert and efface ourselves?

For a clue on how to resolve this dilemma, we can look to nature. When the peacock proudly raises his tail, he doesn’t seem to be thinking, “See this beauty that I myself have created.” In fact, the peacock can’t see his own magnificent body. Rather, the peacock is a vehicle through which life’s beauty is expressed.

We humans differ from the peacock and the azalea in being able to consciously choose and create the way in which we present ourselves. Our human blessing and curse is to view ourselves as the architects of our destinies.

From this vantage point, it’s sometimes difficult to give credit to the larger life force moving within us. To be a yogi, we must find the center point between pride and self-deprecation. To belittle ourselves is to belittle the power of life itself, to turn ourselves into a peacock who refuses to raise his tail feathers. On the other hand, to be arrogant is to take credit for things we didn’t create. Did any of us design the muscles and joints that work together in Pincha Mayurasana?

In the Chinese worldview, human beings stand halfway between heaven and Earth. Like all creatures, we must burst forth and display what is inside us, knowing we didn’t create what is being displayed.

The attitude with which we’re doing Pincha Mayurasana shows in how we practice the pose. If our execution lacks firmness, assertiveness, and determination, the pose will sag and fail. On the other hand, if it’s done with arrogance and an egotistical attitude, the chest may puff forward, destroying the vertical lift. Can you find the midpoint between these two extremes? Can you take your place exactly between heaven and Earth?

How To Prep for Pincha Mayurasana

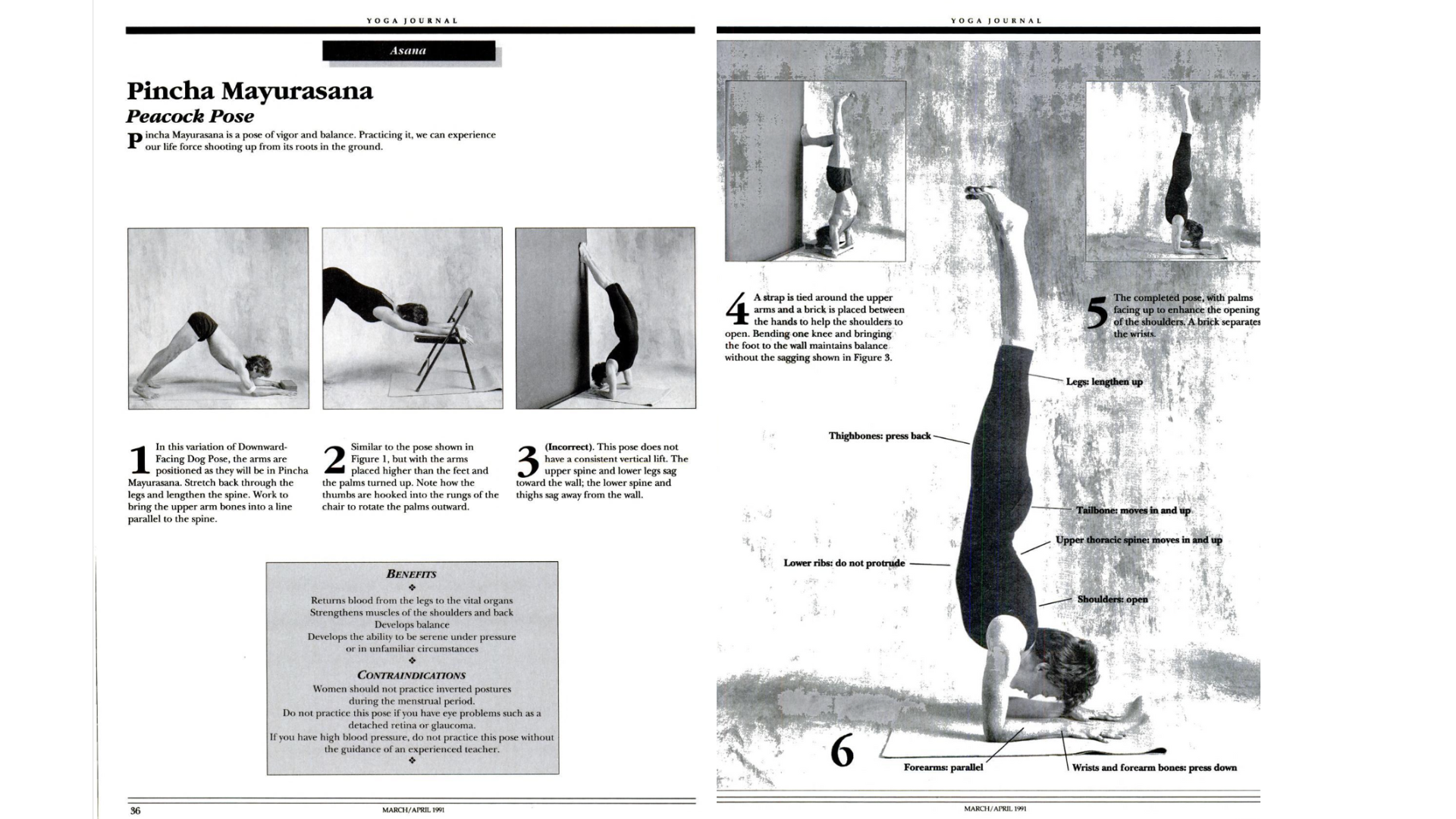

Beginners, your challenge is to open the shoulders and build strength in the upper body by practicing the poses shown in Figures 1 and 2. The second variation (Figure 2) is better for building shoulder flexibility, while the first variation (Figure 1) is better for building upper body strength.

Figure 1

This is a variation of Downward-Facing Dog in which the forearms and palms are in contact with the ground, with the elbows shoulder-width apart, as they will be in Pincha Mayurasana. Stretch back through the legs and lengthen the spine. Work to bring the upper arms into a line parallel to the spine.

A strap around the upper arms can be used to hold in the elbows, which tend to splay out to the sides. In people with stiff shoulders, the hands tend to pull together, as though joined by a spring. A block placed between the hands will help keep them apart, which also assists in opening the shoulders. Hold this pose for 1 to 3 minutes with even breathing, elongating the spine and trying to draw your weight back into the legs. This variation builds the strength and flexibility of the upper body that will be required for Pincha Mayurasana.

Figure 2

Now try doing the same pose but with the forearms resting on a chair seat rather than on the ground, palms facing upward. The feet are on the floor and the pelvis and legs are placed just as they are in Figure 1. Without actually moving your feet farther back, imagine that invisible hands are tugging on your thighs, drawing them back away from the chair. If you create this feeling, your spine will lengthen and the upper arms will run more parallel to the spine. This second variation allows the shoulders greater opening than in the first variation.

The second factor contributing to greater shoulder opening is that the palms face upward, not downward as in Figure 1. Point your thumbs down toward the ground and then hook them against the back legs of the chair. The palms should appear to be rolling outward, rather than facing straight up to the ceiling.

This action, which might appear to come from the wrist joints, in fact originates from the shoulders. To educate yourself about how the shoulders move, try this variation first with palms facing up, then with palms facing down. When the palms face up, you should feel that the shoulders release away from the ears more freely and the shoulder blades spread farther away from the spine. This freedom in the shoulders is integral to the practice of Pincha Mayurasana. If this variation causes pain in the wrists, the shoulders aren’t opening properly. Ask an experienced teacher for help.

Master the actions shown in Figures 1 and 2 before trying to do the completed pose.

How to Practice Pincha Mayurasana

Pincha Mayurasana is a pose of vigor and balance that promotes balance, strengthens the muscles of the shoulders and back, and develops the ability to be serene under pressure or in unfamiliar circumstances.

Do the Downward Dog variation with your middle fingertips touching a wall. Then, keeping the shoulders open as you’ve learned to do, kick one leg up to the wall, allowing the second leg to follow. (Caution: Your head must be off the ground. If you can’t keep your head off the ground once you kick up, go back and practice the variations shown in Figures 1 and 2 for a few weeks.)

Do not practice Peacock Pose if you have eye problems, such as a detached retina or glaucoma. If you have high blood pressure, do not practice this pose without consulting with your physician.

Figure 3

The first time most of us “succeed” in getting into the basic shape of Pincha Mayurasana, we look like the model in Figure 3. This photo demonstrates what you do not want to do. Her body is forming the much-dreaded “banana” shape and does not have a consistent vertical lift. The upper spine and lower legs sag toward the wall; the lower spine and thighs sag away from the wall. Notice that her upper arm bones are not directly underneath her torso. No engineer in the world would build a structure like this one, with the supporting columns off to the side of the building. Here the muscles, rather than the skeleton, are carrying the body’s weight.

To save yourself from this horrible fate, you must open your shoulders by practicing the variations given earlier. You can correct this by looping a strap around the upper arms and placing a brick between the hands to help the shoulders to open. Bending one knee and bringing the foot to the wall maintains balance without the sagging shown in Figure 3.

Figure 4

In this pose, your torso, legs, and feet will be in better balance if they’re aligned above your elbows, not above your hands, as in Figure 3. For this reason, I suggest that until you are somewhat familiar with the pose, you bring one foot against the wall and bring the other directly over the torso (Figure 4). Bend the one leg at the knee and place the entire foot against the wall with the lower leg parallel to the floor. This position gives you a feeling of direct vertical extension in the other leg, which is integral to the pose. Eventually, you will no longer need the wall for support.

This variation ensures that the legs rather than the arms will continue to bear most of the body’s weight. The shoulder joint is thus freer to move, and the muscles surrounding it can “breathe” and stretch.

Press the forearms firmly into the ground. Turn the head to look at the floor. Actively stretch up through the legs and tuck the tailbone into the body. The breastbone should move away from the wall. The lower rib cage (nearest the abdomen) and the top thighbones should move a little back toward the wall. The guiding principle should be that the body should feel like it is shooting upward.

While you’re patiently developing the flexibility of your shoulders and upper back, a strap and a block come to the rescue. To begin practicing this pose, use props as you did in the Downward Dog variation shown in Figure 1. The strap holds the upper arms to shoulder width; the block keeps the hands apart. Gradually work to bring your second leg away from the wall, lifting it up to join the other leg.

Figure 5

Also try the variation shown in Figure 5, in which the hands are placed with the palms facing upward, as we did in Figure 2 earlier. To hold the hands apart, place a block between the wrists and the first two inches of the forearms. (The block will be less effective if merely placed between the hands.)

Those with stiff shoulders may find this variation difficult, whereas those with more flexible shoulders may be surprised to discover that this variation is actually easier for them than the basic pose. Provided the shoulders don’t resist it, this positioning makes it casier to get into the pose, easier to extend fully, and easier to hold the pose for a longer period of time. The ease comes because the variation encourages the shoulders to open better, and thus the pose requires less muscular strength.

Figure 6

Once you can consistently balance well near the wall, try coming up into the pose in the center of the room. In Figure 6, the model’s bones are much closer to lining up one above another, with the upper arms solidly beneath the torso.

The flexibility of her shoulders makes this alignment possible. Pincha Mayurasana illustrates how strength is sometimes improved by developing flexibility. Because this model’s “building” is “well-engineered,” she doesn’t have to work as hard to hold it up.

Initially, any variation of Pincha Mayurasana will produce some strain in the throat and sense organs. As your practice develops, work toward leaving the brain in a state of Savasana (relaxation), even as the body becomes more extended and powerful. Remember the example of the peacock: Express magnificence, while not seeing yourself as the creator of that magnificence. Become a witness of the pose being created—within you, but ultimately not by you.