Published January 21, 2026 09:25AM

Yoga Journal’s archives series is a curated collection of articles originally published in past issues beginning in 1975. This article first appeared in the December 2002 issue of Yoga Journal.

Throughout India, you’ll find statues of Lord Shiva, arch-yogi of the Hindu gods. Most often, he’s shown in the guise of Nataraja, king of the dancers, balanced on one foot and gesturing with all four hands. From region to region, the deity’s features may change—after all, no one knows the true face of god—but his hand gestures never vary. In Indian art, these hand gestures, called mudras, are the true signatures of the gods and saints. And the use of these gestures, along with many others, are a powerful but often-neglected part of traditional yoga practice.

In India, as in many cultures including our own, hand gestures are a vital component of religious activity. As you regard a statue of the dancing Shiva, the tranquil beauty of a meditating Buddha, or any of the innumerable Hindu deities and Buddhist bodhisattvas, notice that each figure holds a stylized hand gesture.

These gestures not only lend gracious expression to India’s iconic art, they also tell stories and represent specific spiritual attributes. Famous Indian art historian Ananda Coomara-swamy called mudras “an established and conventional language in India.” Though quite a bit easier to learn than Sanskrit, the language of mudra also traces back at least to Vedic times.

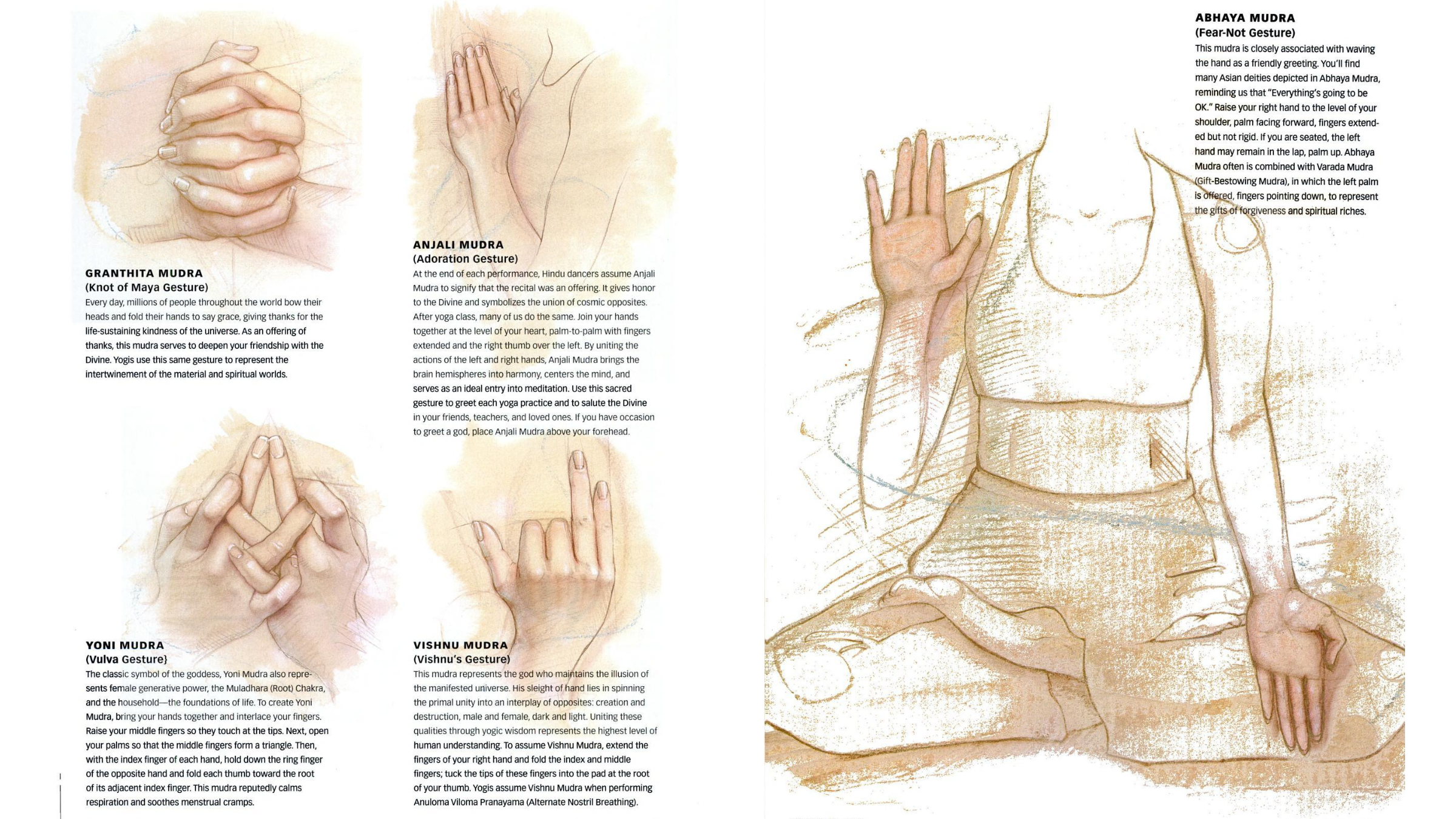

Though nobody really knows how long ago hand gestures began to signify both religious and secular ideas, many expressive gestures used today—asking for calm and silence by raising a palm or emphasizing a point by lifting an index finger—echo ancient ceremonial traditions. In yoga, mudra evolved into a complex symbolic language that serves two purposes: transmitting esoteric concepts and, literally, embodying spiritual ideals. Probably the most common yoga mudras are those used in meditation poses.

These include the Nana Mudra (Wisdom Gesture; also known as Chin Awareness) that symbolizes the union of individual self with God, and the Vishnu Mudra (see below) used in Alternate Nostril Breathing (Nadi Shodhana). But there are many others—108, according to some yogic lore. Some of these mudras are incorporated into asana practice.

For example, when you join your palms over your head in Sun Salutation (Suryanamaskar), your hands are in the yogic gesture known as Anjali Mudra, used to invoke and greet the gods. When you bring your palms down in front of your face, you are in the proper mudra for greeting your elders. And when you lower your palms to your chest in Namaste, you are in position to “salute the Divine” in your peers.

Symbolic Hand Gestures Span History

Although less practiced in the West than asana (poses) and pranayama (breathing practices), mudra can add many layers of depth to your yoga. It is a subtle form of asana that reaches back to yoga’s Indian roots and connects you with a deep, universal mode of human expression. Some yogis claim that mudras possess healing powers; others claim that they cultivate paranormal abilities. Whatever the validity of such claims, it’s clear that the gestures you make influence your state of mind. Try this experiment: As you sit, lean forward, place your left forearm across both thighs, and cup your right elbow in your left palm. Now rest your chin in your right hand, between the thumb and forefinger. You’ve just assumed the “thinking mudra” immortalized in Rodin’s famous statue. And if you stay in this position for a few minutes, you may also find yourself falling into a more contemplative frame of mind. Now sit up and wave your right hand in the air, as if greeting a friend in the distance. You may discover a smile and a friendly feeling naturally arise with this gesture.

Gestures do much more than communicate ideas; they also embody emotions. And just as speech can become a vehicle of spirituality through prayer, gesture can become prayer through the practice of mudra. When you use Jnana Mudra in meditation, for instance, the featherlight touch of thumb and forefinger provides a focal point that helps you concentrate; if you know that the thumb traditionally symbolizes all things divine and the index finger your individual self, maintaining the connection becomes both a reminder and an embodiment of this sacred union.

The Universal Language

Of course, yoga is not unique in using hand gestures as a means of sacred expression. Egyptian priests also used mudras to communicate with their gods. The Greeks choreographed elaborate hand signals into their plays. The Roman citizen orator trained to become an accomplished gesturer as well as a persuasive speaker. Native Americans and Australian aborigines each developed a vivid “sign talk” that once served as a lingua franca between tribes and that still survives as an integral feature of storytelling. Hand signals occur in every culture on Earth and may even hold a key to the origins of human communication.

We react to hand gestures extremely quickly because certain nerve cells in the lower temporal lobe of our brains are dedicated exclusively to responding to hand positions and shapes. The site of these cells, deep in a relatively primitive part of the brain, suggests that gesture may predate words in evolutionary history as a means of human expression. Evolutionary linguist Sherman Wilcox, Ph.D., coauthor of Gesture and the Nature of Language (Cambridge University Press, 1995), speculates that “Language emerged through bodily action before becoming codified in speech.”

Wilcox describes modern human communication as a holistic, “aural-gestural” method of expression. “Children acquire gesture and language skills simultaneously,” Wilcox explains. Many of our hand gestures are actually activated from the primitive speech areas of the right brain. This neurological cluster plays a much less important role once our language functions shift to the left hemisphere in early childhood, but the right hemisphere cluster remains connected to the expressive movements of our hands. Throughout life, speech and gesture cooperate to convey meaning. That’s why without gesturing, we do not feel as if we have expressed ourselves fully.

But because gestures don’t pass through the left-brain language filters, our hands often convey shades of meaning we don’t consciously intend. There’s a maxim among bodyworkers and body-centered therapists: “The body seldom lies.”The late John Napier, M.D., an authority on the evolutionary history of manual dexterity, made a similar observation: “If language was given to men to conceal their thoughts, then gesture’s purpose was to disclose them.”

Most of us are keenly sensitive to the very subtle connotations conveyed by the slightest turn of a shoulder or a dismissive flick of the wrist. Flirting, joking, bargaining—indeed, practically every kind of social interaction—require reading nonverbal cues. Like simple “body language,” hand gestures reveal aspects of the inner life that lend nuance to speech. Brain-imaging studies show that hand gestures precede speech in what neurologists call “deep time”—which is just an evocative way of describing the moment before you become conscious of your own thoughts. In other words, the impulses for gestures form in your brain before those for words do.

The hands express what neurologists call the “imagistic” process of thought. During that moment of deep time before your thoughts turn into words, your ideas emerge as concrete images and feelings. For example, when you’re trying to convey a difficult abstract idea, you might hold your hands in front of you as if you are shaping a container for the thought. The more abstract the thought, the more intensely you’ll use your hands to “get hold of it,” as if an idea had substance that could be grasped. Our hands help make abstract concepts concrete so we can process them more easily, says Wilcox. Words represent ideas; gestures embody them.

In Wilcox’s view, gestures are thinking in action. One of the foremost researchers in gesture, linguist David McNeill, echoes this perspective when he refers to gestures as a form of thought—not just an expression of thought, but “cognitive being” itself. This embodiment is especially important when we try to communicate ineffable spiritual ideals that can’t be fully understood until we’ve experienced them. For a spiritual concept to have deep transformative power, it must become tangible and grounded in the body.

The late Swami Sivananda Radha, the first Western woman initiated into Swami Sivananda’s monastic order, described the transformational power of asana by saying that when “an asana is perfected through practice, at a certain point it becomes spiritual—a mudra.” In other words, in its ideal form each asana places the body in a configuration that helps to induce and reinforce a specific state of higher consciousness. And indeed, though in modern usage “mudra” generally refers to hand gestures, it can also refer to practices ranging from specific asanas to the energy locks more often called bandhas.

In each case, the mudra acts as a container that holds and stamps a specific energetic state into the body. Etymologically, “mudra” derives from Sanskrit roots that mean “to give joy,” but most yoga authorities say the term originally derives from an Assyrian word for an imprint used in writing. This became the Sanskrit word for the stamp or seal that Indian kings used to authenticate royal decrees. By extension, “mudra” signifies a spiritual seal that expresses and “authenticates” a yogi’s internal state.

Swami Sivananda Radha’s description of the transformative power of gesture finds an interesting extension in a recent discovery by a group of neuroscientists working in Italy. They found that observing a gesture could stimulate the same patterns of neural firing as when actually performing it. They called this phenomenon “mirror neurons.” Wilcox speculates that mudras just might work in the same way. Once a spiritual state is associated with a gesture through practice, just looking at the gesture—depicted in an icon or performed by someone else—could trigger your mirror neurons to recreate the spiritual state.

The Evolution of Mudras

Despite the importance as a universal element of human communication, nobody really knows how hand gestures evolved into a form of yoga. Scholars speculate that mudras may have developed from one of three sources: shamanic dance, the ancient mimetic hand gestures that accompanied Vedic chanting, or perhaps the hand movements prescribed in the Vedas to handle ceremonial tools during sacrificial rites. According to some historians, the asana tradition itself derives from the practice of these ritual hand gestures in pre-Vedic times. Asanas, in this view, represent the evolution of mystic gestures into full-body “seals.”

These days, mudra joins asana and mantra (sacred words chanted or repeated silently) as a tool to help facilitate the inner attitudes a yogi endeavors to cultivate. But only a few present-day yoga schools in the United States regularly and systematically include mudras in their practice. Baba Hari Dass, a revered Indian yogi and inspiration for the Mt. Madonna community and retreat center near Watsonville, California, instructs his students in the use of 24 devotional mudras performed prior to meditation, followed by eight immediately after. According to the teachings of Yogi Bhajan, Kundalini Yoga considers mudra an essential component of yoga, along with exercises, pranayama, mantra, and meditation. Practitioners of Kundalini Yoga regularly use numerous mudras to stimulate the ethereal body.

And the hatha yoga aspect of Kali Ray’s Tri Yoga system is based on a trinity of practices: asana, pranayama, and mudra. Beginners start with 20 mudras and progress through hundreds more, many of which Ray says she discovered through the spontaneous movement of energy through her body during meditation.

Mudras Help Tell Stories

The use of mudra in yoga has deep connections with the formalized gestures of Indian classical dance. Though gesture-dance has become largely an aesthetic expression in modern Indian culture, generally staged in dance halls and theaters, it was born as a form of yoga in the Shaivite temples of South India. Legend traces the creation of sacred dance to holy seers and priests at the dawn of Indian history. The Bharata Natya Sastra, the oldest classical treatise on Indian theater, says that Lord Brahma, the primal Creator, offered dance as a means of communicating the knowledge of Vedic lore to all castes.

To accomplish this, the temple dancer employs a sacred vocabulary of hand gesures called hastas to tell stories about the Divine.

“In Western dance traditions, the teacher offers to show you the steps, but the Indian dance teacher offers to show you the hands,” says Gitanjali Kolanad, an internationally acclaimed dancer of Bharata Natyam (Indian Dance Theater). The role of the dancer, explains Gitanjali, is to use gesture to “express the states of the soul.” These states are referred to as bhava. A skilled dancer conveys the narrative elements of the story and its bhava to her audience through gesture. The stories often center on either Vishnu or Shiva, the sustaining and destroying aspects of the Hindu trinity. According to Gitanjali, the purpose of the stories “is to bring the audience into a sacred space where each observer can experience the deity in person, as if the dancer were Vishnu or Shiva incarnate.”

This transmutation of dancer into divinity occurs gradually and culminates when the dancer assumes the god’s mudra. Gitanjali differentiates between these mudras and other hand gestures, which she refers to as hasta (literally, “hand”).

“Hasta tells the story,” explains Gitanjali, “but the story leads to a climax with the hand gesture that is the signature of the god. If the dancer is skilled and the audience attentive, the god is made flesh in the theater.”

Spontaneous Mudras

Athough the use of mudra in both Indian dance and traditional yoga has been passed down for generations as a highly formalized practice, some yogis say that mudra can also arise as a natural and spontaneous expression when kundalini, the “serpent energy” that lies sleeping at the base of the spine, is awakened.

Just as hand gestures occur spontaneously to help us express meaning when we speak, these more esoteric spontaneous gestures manifest spiritual states. In 1980, Kali Ray knew only one mudra, the classic Jnana Mudra of meditation. But one evening, as she sat in Lotus Pose, guiding her class through a visualization of kundalini uncoiling at the base of the spine, she found that her own kundalini stirred and surged through her body.

Ray suddenly began performing a series of gestures that she sees as spontaneous, kundalini-driven mudras. While some of these gestures resembled classical yoga mudras, others did not. In later years, she repeated the same “channeling” phenomenon. Five years ago, this culminated in a cathartic three-day-long trance during which she expressed more than 800 distinct mudras.

Though this experience might sound like a fanciful tale or a modern innovation, it actually harks back to a medieval school called Sahaja Yoga, generally translated as “Spontaneous Yoga.” The Sahaja yogis believed that enlightenment comes only through internal spontaneity and not external discipline. Meditations involving unstructured, ecstatic dance were characteristic of this school. Stuart Sovatsky, director of the Kundalini Clinic in Oakland, California, and author of Words from the Soul: Time, East/West Spirituality, and Psychotherapeutic Narrative (State University of New York Press, 1998), says that mudra derives from these spontaneous, prana-driven dances.

In Sovatsky’s eyes, using mudra as a codified formal practice meant to induce kundalini awakening is something of a backward approach. A modern-day Sahaja yogi, he likens this method to “standardizing the forms for the human smile or frown.” Sovatsky suggests that-just as Ray experienced—mudras are best understood as “gestures of delight” animated by prana, rather than as a means to control kundalini.

Ray says that mudra can work both ways, “Inside out or outside in.” In other words, a mudra can spontaneously express a higher state of consciousness, but the same mudra can also be used to consciously induce that state. Ray’s students start with a simple practice of classic yoga mudras; some eventually experience the spontaneous arising of kundalini-inspired spiritual gestures. Ray teaches individual mudras and combines them together in fluid sequences, much like vinyasa asana practice.

The effect of mudra comes through stimulating the ethereal body, Ray explains. The fingers represent each of the five senses, elements, and pranas (vital energies). The three segments of the fingers represent the gunas, or constitutional qualities, of the individual: sattva (purity), rajas (activity), and tamas (dullness). By touching various points on the fingers and thumbs, the subtle body can be stimulated and eventually brought into equilibrium.

Along with providing such health and subtle energy benefits, basic yoga mudras can help deepen your yoga practice. Both formal mudra practice and more free-form exploration of the expressive potential of the hands can help create the inner alchemy of spiritual transformation. Every gesture can be read as a message from the mind’s “deep time,” where the self articulates truths the ego may not yet know. As you continue to develop this practice, you can strive to make every action of your hands a mudra— a living prayer.