Published February 4, 2026 01:27PM

Yoga Journal’s archives series is a curated collection of articles originally published in past issues beginning in 1975. This article first appeared in the July-August 1984 issue of Yoga Journal.

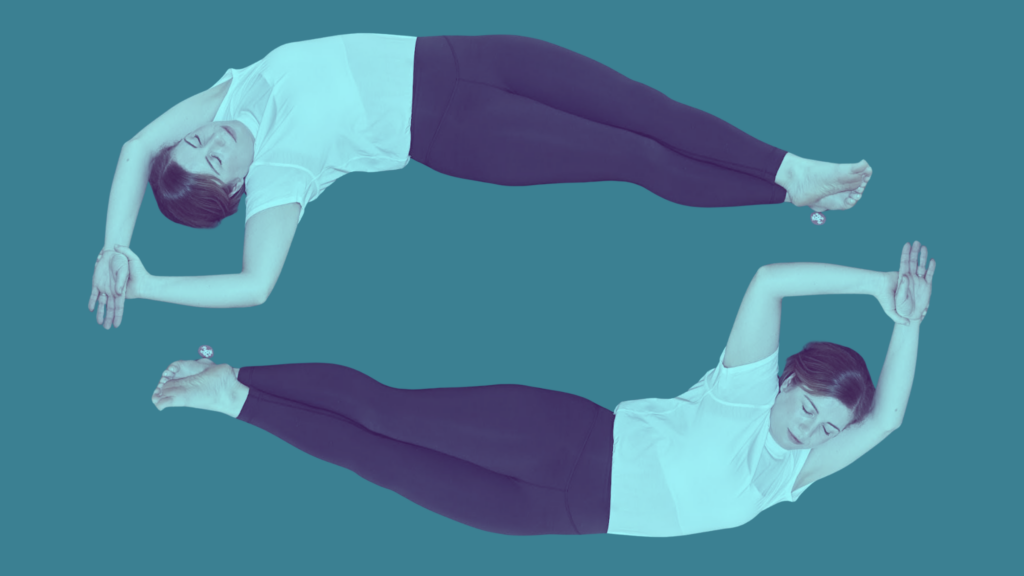

Headstand (Sirsasana) is often called the “king of poses” because of the many benefits it affords. It teaches balance and poise, increases the strength of the arms, positively affects the cardiovascular system, and allows, more than many poses, a few minutes for mental and physical stillness. It’s a difficult pose, involving many precautions and prerequisites. Many Westerners feel that if they can practice Headstand, they are practicing “real” yoga.

But is it really such an essential part of a daily yoga practice? It depends on who you ask. Headstand feeds the brain not only blood, but a subtler form of energy as well. After the practice of Headstand, the mind and body feel nourished, and the nervous system is quiescent. When this occurs, the student comes to understand that yoga is not something one does but a state one is. Headstand is then no longer something external, to be mastered or conquered; it becomes the perfect expression in form of the essence within.

Still, it is not for the beginning student. Learning to keep just the right amount of curve in the neck is one of the most important points of Headstand, not only because the cervical spine must be protected, but also because it is here that the balancing begins.

The Benefits of Headstand

The benefits of Headstand are related in large part to the change in blood flow in the body and to the improvement in balance that can be learned by the nervous system. There is some evidence that the practice of Headstand over time can reduce arterial blood pressure by helping to reset the pressure-regulating reflexes. In addition, Headstand helps to increase venous return to the heart, bringing the deoxygenated blood toward the heart and relieving pressure in the passive venous system caused by the pooling of blood in the legs during standing.

Headstand also affects the balancing mechanism; just as a child learns to walk and balance vertically, Headstand teaches the adult yoga practitioner poise and balance and requires concentration and practice to achieve. This process of concentration is an important, if not crucial, aspect of the study of yoga as a whole.

Headstand must be practiced correctly to avoid problems with the cervical spine, which normally bears only the weight of the head – approximately 20 pounds. In a properly balanced Headstand, although the weight is in fact diffused through the arms, neck, and head, one will have the sensation that the weight is borne by the head, not the neck. In fact, the cervical spine should feel free; it should be positioned in such a way that it maintains its normal curvature.

If the cervical spine has too much of an arch in Headstand, weight moves too far to the rear portion of the spine, where the spinal nerves exit the cord. If the cervical spine is too flat, weight falls too far to the anterior segment of the spine, the intervertebral discs. Neither of these alternatives is desirable, because this change in weight decreases the stability of the spinal column, causing the surrounding musculature to tighten in an attempt to create stability. This decreased stability may allow a vertebra to move out of place and may lead to excessive muscle tension.

Headstand is also an important pose for teaching a balanced perspective. In Headstand, one cannot see the body and how it is aligned, as in other poses. One can only look outward and make adjustments from the inside; there is little external feedback.

The only visual perception one has in Headstand is one’s relationship to the external world. Thus Headstand can be a time to examine how one interacts and reacts in relation to the outside world, while maintaining awareness of the inner world, thus creating balance. Learning to understand the relationship between the inner and outer is as important in practicing Headstand as in learning loving interaction with others. Perhaps this dual awareness is the true “balance” of Headstand.

Finding Safety in the Pose

The most important point to remember while going into, holding, and coming out of Headstand is that the cervical spine (neck) must be maintained as much as possible in its normal curve, which is concave posteriorly (on the back). If this curve cannot be maintained, one runs the risk of incurring strain or injury to the cervical region.

An overly straight, flattened cervical spine in Headstand throws too much weight onto the intervertebral discs; too much curve in the neck puts excessive weight on the facet joints, the small, flattened joints at either side of the posterior vertebrae. Both these actions are to be avoided because they increase wear and tear on delicate cervical structures.

Most students are concerned with balancing the trunk or the legs, when actually the point of true balance is the contact between the skull and the first cervical vertebra. Balancing the vertebral column on the skull is akin to balancing a stick on a ball. If the stick is in the correct relationship to the ball, the rest of the stick will be aligned. Therefore, care should be taken to maintain the natural curve of the neck during the entire process of Headstand. Not only will this serve to protect the cervical spine, but it will enhance balancing as well.

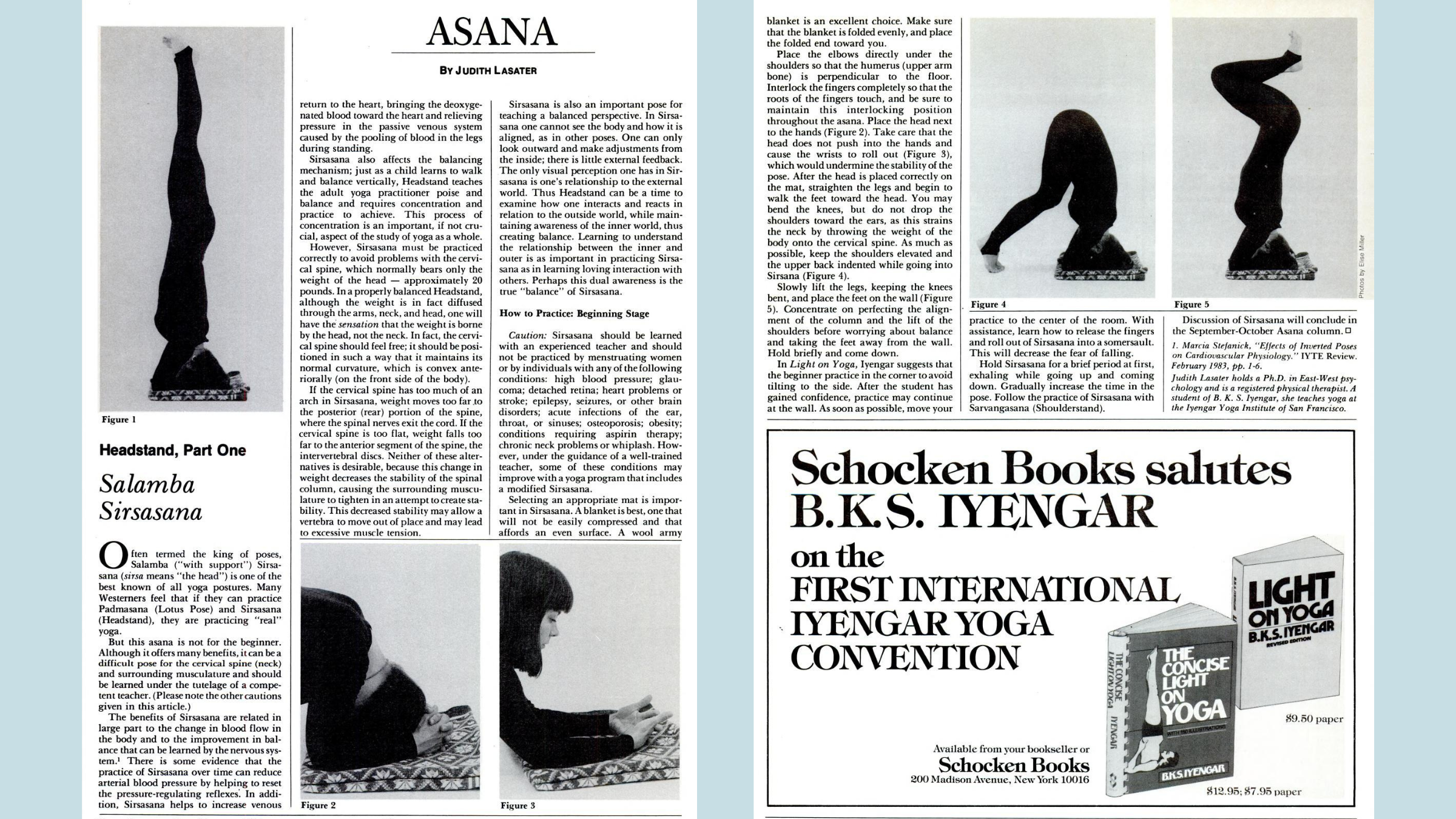

Another important prerequisite to learning Headstand is flexibility in the upper back and thoracic spine. In Figure 5 (below) the spine is too rounded in the middle; this throws too much weight onto the cervical spine. The neck appears to have disappeared. Also important is flexibility in the hamstring muscles in the back of the thighs, especially if the student is trying to come up with straight legs. If hamstrings are tight, the pelvis cannot lift up properly, thus causing the thoracic spine to round and the cervical spine to bear too much weight.

Finally, the student should have sufficient arm strength, which can be developed from correct use of the arms in standing poses and from Sun Salutation, in which weight is borne by the arms. If all these basic conditions are met, the student should be ready to practice Headstand.

How to Practice

Selecting an appropriate mat is important in Headstand. A blanket is best, one that will not be easily compressed and that affords an even surface. A wool army blanket is an excellent choice. Make sure that the blanket is folded evenly, and place the folded end toward you.

Note: Headstand should be learned with an experienced teacher. Those experiencing any of the following conditions or who have concerns should consult a physician prior to attempting Headstand: chronic neck issues; high blood pressure; glaucoma; detached retina; heart problems or stroke; epilepsy, seizures, or other brain disorders; osteoporosis.

Half Headstand

Place the elbows directly under the shoulders so that the humerus (upper arm bone) is perpendicular to the floor. Interlock the fingers completely so that the roots of the fingers touch, and be sure to maintain this interlocking position throughout the asana. Place the head next to the hands (Figure 2). Take care that the head does not push into the hands and cause the wrists to roll out (Figure 3), which would undermine the stability of the pose. After the head is placed correctly on the mat, straighten the legs and begin to walk the feet toward the head. You may bend the knees, but do not drop the shoulders toward the ears, as this strains the neck by throwing the weight of the body onto the cervical spine. As much as possible, keep the shoulders elevated and the upper back indented while going into Sirsana (Figure 4).

Slowly lift the legs, keeping the knees bent, and place the feet on the wall (Figure 5). Concentrate on perfecting the alignment of the column and the lift of the shoulders before worrying about balance and taking the feet away from the wall. Hold briefly and come down.

In Light on Yoga, Iyengar suggests that the beginner practice in the corner to avoid tilting to the side. After the student has gained confidence, practice may continue at the wall. As soon as possible, move your practice to the center of the room. With assistance, learn how to release the fingers and roll out of Headstand into a somersault. This will decrease the fear of falling.

Hold headstand for a brief period at first, exhaling while going up and coming down. Gradually increase the time in the pose.

Full Headstand

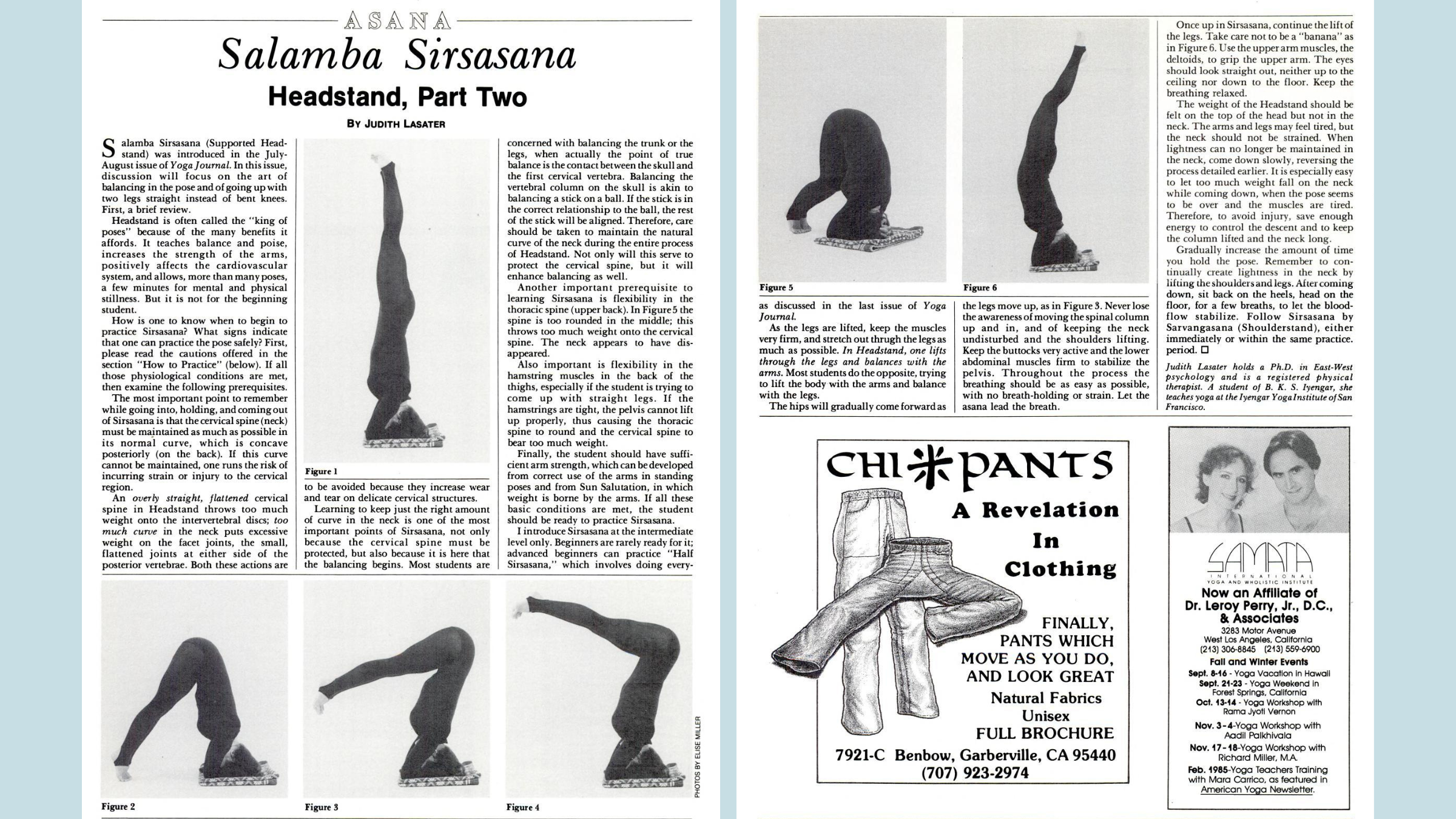

Begin by practicing near a wall, gradually moving out to the center of the room. After selecting a firm mat, placing the elbows near the shoulders, and interlocking the fingers well, place the head next to the hands. Straighten the knees while simultaneously lifting the shoulders, as shown in Figure 2. Take care that none of the movement disturbs the hands or wrists. Remember that the thoracic spine should not appear as in Figure 5. Lifting the shoulders must be accompanied by a lifting of the upper back so that the vertebral column is elongated from neck to lower back (Figure 2).

On exhalation, begin to walk the feet toward the body. The hips will move back over the head, and the legs will lift automatically. If this movement is a struggle, then practice with the knees bent. As the legs are lifted, keep the muscles very firm, and stretch out thrugh the legs as much as possible. In Headstand, one lifts through the legs and balances with the arms. Most students do the opposite, trying to lift the body with the arms and balance with the legs.

The hips will gradually come forward as the legs move up, as in Figure 3. Never lose the awareness of moving the spinal column and in, and of keeping undisturbed and the shoulders lifting. Keep the buttocks very active and the lower abdominal muscles firm to stabilize the pelvis. Throughout the process the breathing should be as easy as possible, with no breath-holding or strain. Let the asana lead the breath.

Once in Headstand, continue the lift of the legs. Take care not to be a “banana” as in Figure 6. Use the upper arm muscles, the deltoids, to grip the upper arm. The eyes should look straight out, neither up to the ceiling nor down to the floor. Keep the breathing relaxed.

The weight of the Headstand should be felt on the top of the head but not in the neck. The arms and legs may feel tired, but the neck should not be strained. When lightness can no longer be maintained in the neck, come down slowly, reversing the process detailed earlier. It is especially easy to let too much weight fall on the neck while coming down, when the pose seems to be over and the muscles are tired.

Therefore, to avoid injury, save enough energy to control the descent and to keep the column lifted and the neck long. Gradually increase the amount of time you hold the pose. Remember to continually create lightness in the neck by lifting the shoulders and legs. After coming down, sit back on the heels, head on the floor, for a few breaths, to let the blood-flow stabilize.